All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the Lymphoma Coalition.

The lym Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the lym Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The lym and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Lymphoma & CLL Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by AbbVie, BeOne Medicines, Johnson & Johnson, Miltenyi Biomedicine, Nurix Therapeutics, Roche, Sobi, and Thermo Fisher Scientific and supported through educational grants from Bristol Myers Squibb, Lilly, and Pfizer. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View lymphoma & CLL content recommended for you

Chronic lymphocytic lymphoma: An overview

Do you know... Which of the following symptoms does not indicate the patient requires treatment after a diagnosis of CLL?

Chronic lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL) is a mature B-cell neoplasm characterized by progressive accumulation of monoclonal B lymphocytes.1 As the most prevalent leukemia in the Western Hemisphere, several novel targeted therapies have been developed for CLL over the past decade, such as Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors (BTKi), B-cell lymphoma 2 inhibitors (BCL2i), and phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitors (PI3Ki). Such therapies have fundamentally changed the therapeutic landscape and significantly improved the prognosis for patients with CLL.1

Etiology

While the exact cause of CLL is unknown, multiple genetic mutations may contribute to altering the DNA of blood-producing cells; this impacts their function.1,2 The most common chromosomal aberrations reported in patients with CLL include either deletion or loss of part of:

- chromosome 11;

- chromosome 13; and/or

- chromosome 17

Parents, siblings, or children of patients with CLL are at a 5–7 times greater risk of developing CLL2.

Epidemiology

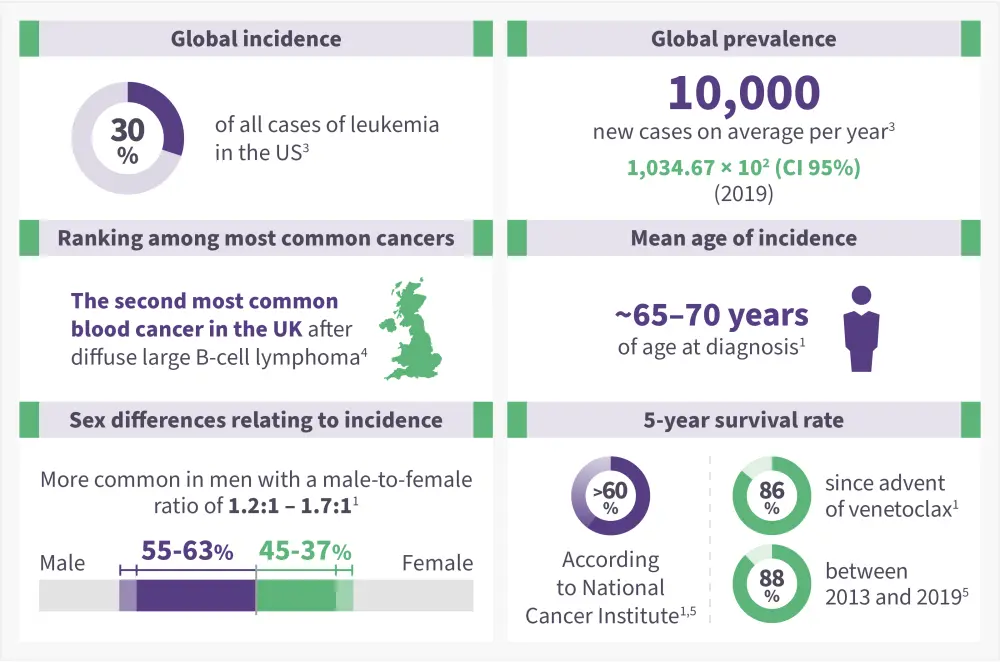

CLL is considered to be a cancer that (Figure 1)1

- Occurs in the elderly population, with a median age at diagnosis of ~70 years.

- Varies in incidence by race and geographic location (higher among Caucasians and extremely low in Asia).

- Accounts for approximately 25–35% of all leukemias in the US.

Figure 1. Epidemiology of CLL*1,3-5

Pathophysiology

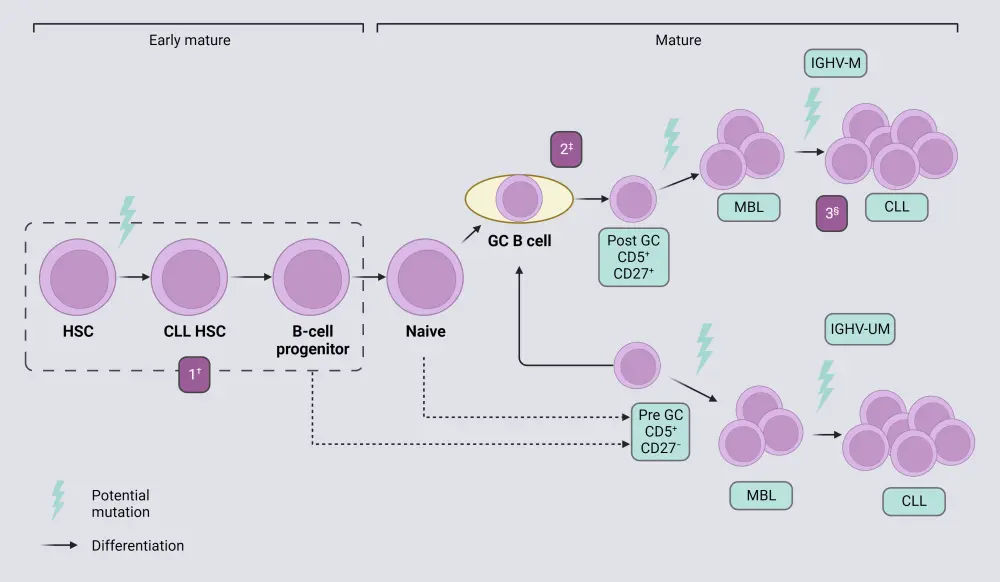

The pathophysiology of CLL involves (Figure 2) 6

- Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) differentiate into lymphoblasts and proliferate. Mutations that contribute to the development of CLL may happen at this stage and give rise to B cells with survival and growth advantages.

- Next, the lymphoblasts differentiate into prolymphocytes and proliferate. If no mutations were present in the differentiation of HSCs to lymphoblasts, there is another chance for an oncogenic event to occur here before the lymphoblasts differentiate.

- In the final stage of CLL cell development, prolymphocytes differentiate into B cells and proliferate.

Once fully differentiated and an oncogenic event has occurred, B cells grow and divide uncontrollably in the bone marrow or the bloodstream causing chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells to develop.

Figure 2. Pathophysiology of CLL*

CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; GC, germinal center; HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; IGHV-M, immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region-mutated; IGHV-UM, IGHV-unmutated; IMBL, monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis.

*Adapted from Fabbri and Dalla-Favera.7 Created with BioRender.com

†Expansion.

‡Clonal selection.

§Further clonal selection.

Signs and Symptoms

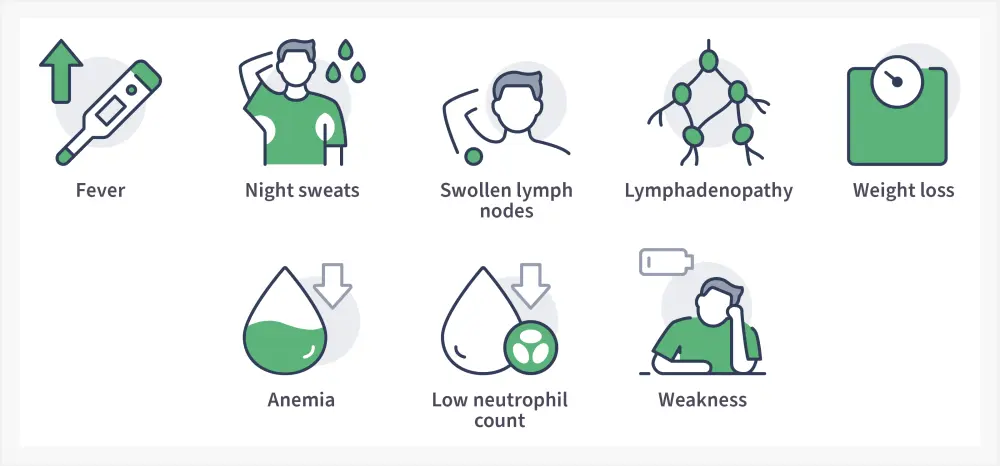

Patients are often asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis but then develop symptoms, as presented in Figure 3.8

Figure 3. CLL signs and symptoms*

Adapted from Shadman.8

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is established by blood counts, blood smears, and immunophenotyping of circulating B-lymphocytes; this can identify clonal B-cell populations carrying the CD5 antigen as well as typical B-cell markers, including CD19/20/23.8 In CLL, the levels of surface immunoglobulin CD20 and CD79b are low compared with normal B cells.8 The diagnosis of CLL is usually confirmed by 8:

- ≥5000 B-lymphocytes/µL in peripheral blood for at least 3 months.

- Clonality of circulating B-lymphocytes confirmed by flow cytometry.

- Small and mature lymphocytes with a narrow border of cytoplasm and dense nucleus lacking distinct nucleoli, and the presence of partially aggregated chromatin confirmed by a blood smear.

- Gumprecht nuclear shadows or smudge cells, found as cell debris.

Risk assessment

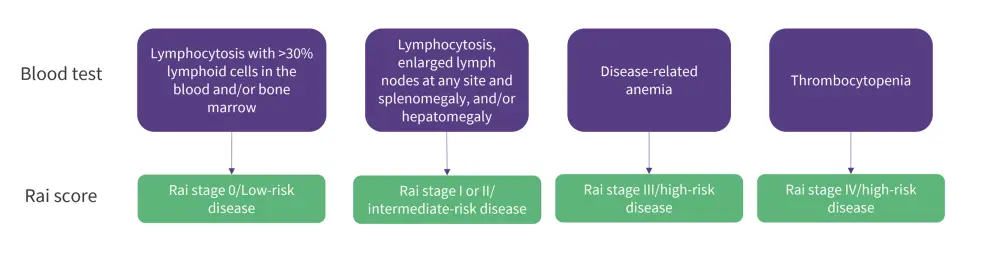

There are two staging systems used to determine the stage of disease: the Rai staging system and the Binet staging system.9 The stages in the Rai staging system are defined in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Rai scoring system*

*Adapted from Hallek, et al. 9

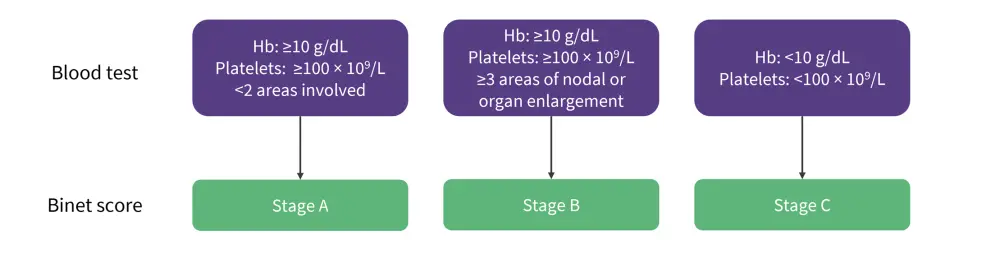

The Binet staging system is based on several areas and defined by the presence of enlarged lymph nodes (>1 cm in diameter) or organomegaly, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. The involved areas include the head and neck, axillae, groins, palpable spleen, and liver. The stages in the Binet staging system are outlined in Figure 5.9

Figure 5. The Binet staging system*

*Adapted from Hallek, et al. 9

Prognosis

Whole genome sequencing has enabled characterization of the genomic landscape in CLL, with prognosis varying according to mutational status.10

- Mutations in the TP53 gene predict resistance to chemoimmunotherapy and a shorter time to progression with most targeted therapies.

- Patients with a del(11q) clone commonly indicates rapid progression, shorter OS, and bulky lymphadenopathy.

- Patients with a del(17p) mutation also present a poor prognosis with low survival rates.

Guidance on diagnosis may vary between countries. Please read below section on key guidelines for further information.

Management

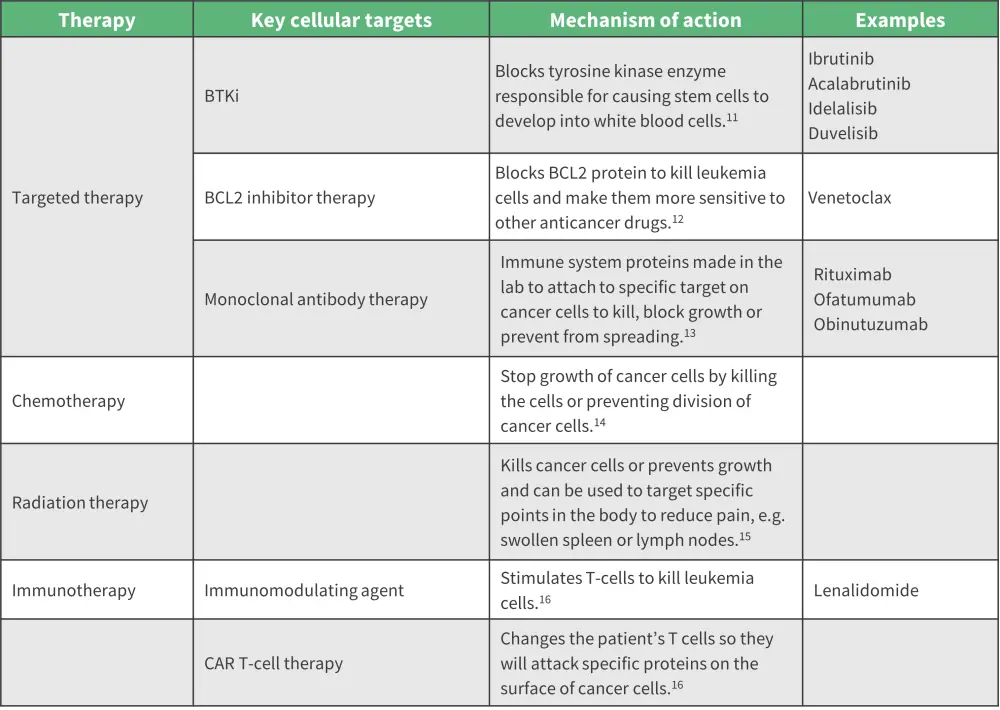

The treatment landscape for CLL has progressed in the last decade. The previously recommended chemotherapeutic agents in combination with a monoclonal antibody have been replaced by targeted agents, such as BTKi and BCL2 inhibitors.10 Figure 6 summarizes the available types of therapy and their cellular targets.

Figure 6. Summary of major types of therapy and cellular targets 11-16

BCL2, B-cell lymphoma 2; BTKi, Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor.

Figure 7. Cancer treatment options*

*Created with BioRender.com

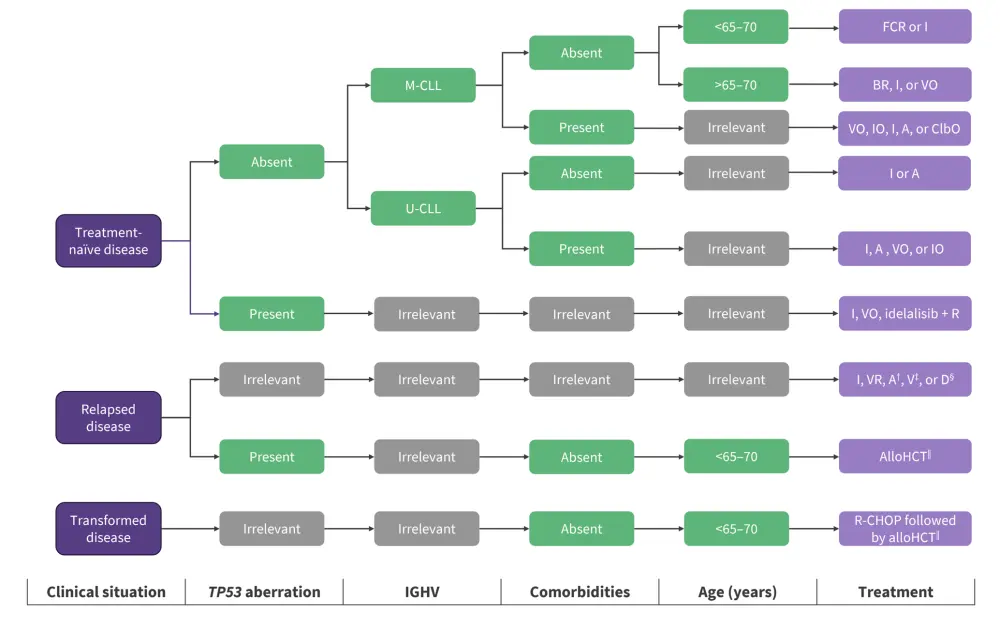

Patients are recommended different treatment options depending on age, comorbidities, and previous lines of therapy.17. Comorbidities are indicated by the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale rating organs for severity and impairment.18

Figure 8. Treatment decisions for different CLL clinical situations*

A, acalabrutinib; AlloHCT, allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation; BR, bendamustine + rituximab; ClbO, chlorambucil + obinutuzumab; D, duvelisib; FCR, fludarabine + cyclophosphamide + rituximab; I, ibrutinib; IGHV, immunoglobulin heavy-chain variable region; IO, ibrutinib + obinutuzumab; M-CLL, mutated IGHV; R, rituximab; R-CHOP, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone; U-CLL, unmutated IGHV; V, venetoclax; VO, venetoclax + Obinutuzumab; VR, venetoclax + rituximab.

*Adapted from Delgado J, et al.17

†Acalabrutinib is approved for both treatment-naïve and relapsed disease by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) but not the European Medicines Agency (EMA).

‡Venetoclax monotherapy is approved for patients with TP53 aberrations who are refractory or intolerant to ibrutinib or patients without TP53 aberrations who are refractory or intolerant to both chemoimmunotherapy and ibrutinib. VR is approved for any patient with relapsed disease.

§D monotherapy is approved for relapsed disease (minimum of two prior therapies) by the FDA but not the EMA.

‖AlloHCT is recommended for appropriate patients with high-risk disease, defined by TP53 aberrations and/or complex karyotype in whom ibrutinib and/or venetoclax has failed. Allogeneic HCT is also recommended for appropriate patients with transformed disease who have responded to salvage chemotherapy (e.g., R-CHOP).

¶Guidance on management may vary between countries.

Key Guidelines and organizations

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network19 published updated CLL/SLL guidelines in 2022. These updates were also covered by the Lymphoma Hub.20. In addition, patient support group pages are available from Cancer Research UK21 and National Organization for Rare Diseases.2

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content