All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the Lymphoma Coalition.

The lym Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the lym Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The lym and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Lymphoma & CLL Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by AbbVie, BeOne Medicines, Johnson & Johnson, Miltenyi Biomedicine, Nurix Therapeutics, Roche, Sobi, and Thermo Fisher Scientific and supported through educational grants from Bristol Myers Squibb, Lilly, and Pfizer. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View lymphoma & CLL content recommended for you

Educational theme│First-line management of patients with cHL: A British Society for Haematology guideline

Do you know... Based on the British Society for Haematology guideline for the management of adult patients with classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL), which would be an appropriate first line of treatment for patients with early favorable disease and a negative interim positron emission tomography (PET) scan?

Hodgkin Lymphoma (HL) is characterized by the presence of Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cells within a cellular infiltrate of non-malignant inflammatory cells and is classified as nodular lymphocyte predominant HL (NLPHL) or classical HL (cHL). cHL has a further four subtypes: nodular sclerosis, mixed cellularity, lymphocyte-rich, and lymphocyte-depleted. Patients with cHL usually present with painless lymphadenopathy and mediastinal disease. Positron emission tomography (PET)/computerized tomography (CT) staging detects bone marrow involvement in up to 18% patients compared to 5−8% of patients using conventional staging. Systemic symptoms such as drenching night sweats, unexplained fever, and weight loss over 6 months are termed as B symptoms occurring in nearly 25% of patients with cHL. Optimal clinical management of patients with cHL has the potential to improve treatment outcomes and quality of life.

As part of the Lymphoma Hub educational theme on the management of HL, here we provide an overview of the first-line management of cHL based on the recently updated British Society for Haematology guideline by Follows et al.1, published in the British Journal of Haematology.

Pretreatment assessment

Patients with a diagnosis of cHL should be assessed prior to treatment (Table 1).

Table 1. Pretreatment evaluation*

|

ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IPS, International Prognostic Score; PET, positron emission tomography. |

|

|

Blood evaluation |

Full blood count including HIV, hepatitis B and C, ESR, renal function, liver function, bone profile |

|---|---|

|

Staging |

With PET scan – A bone marrow biopsy usually not required |

|

Classify early-stage patients as favorable or unfavorable |

|

|

Advanced staged patients – allocate IPS |

|

|

Fertility preservation |

Referral for ovarian tissue, oocyte, embryo, or semen cryopreservation should be considered where appropriate to minimize treatment delays |

Prognosis – Early-stage disease (Stage I and II)

Patients with early-stage disease with adverse features (B symptoms, bulky disease, or multiple nodal sites) have traditionally been managed in the UK with protocols for advanced-stage disease. However, long-term follow-up studies show that these patients have excellent outcomes when treated with early-stage risk-stratified protocols. The pre-treatment evaluation recommended above should determine whether a patient with early-stage disease fits in the favorable or unfavorable category (Table 2). Of note, there is variation in the categorization of mediastinal thoracic ratio; the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) criteria considers this as >0.35 at T5/6, whereas the UK National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) and German Hodgkin Study Group (GHSG) consider this to be >0.33.

Table 2. Favorable and unfavorable prognosis*

|

EORTC, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of cancer; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; GHSG, German Hodgkin Study Group; HL Hodgkin lymphoma. |

|||

|

Favorable prognosis stage I–II HL |

Unfavorable prognosis I–II HL |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

EORTC |

GHSG |

EORTC |

GHSG |

|

Presence of one or more of the following: |

|||

|

No large mediastinal adenopathy |

No large mediastinal adenopathy |

Large mediastinal adenopathy |

Large mediastinal adenopathy† |

|

ESR <50 without B symptoms |

ESR <50 without B symptoms |

ESR ≥50 without B symptoms |

ESR ≥50 without B symptoms |

|

ESR <30 with B symptoms |

ESR <30 with B symptoms |

ESR ≥30 with B symptoms |

ESR ≥30 with B symptoms |

|

Age ≤50 |

No extranodal disease |

Age >50 |

Extranodal disease |

|

1–3 lymph node sites involved |

1−2 lymph node sites involved |

≥4 lymph node sites involved |

≥3 lymph node sites involved |

Management

Early-stage favorable disease

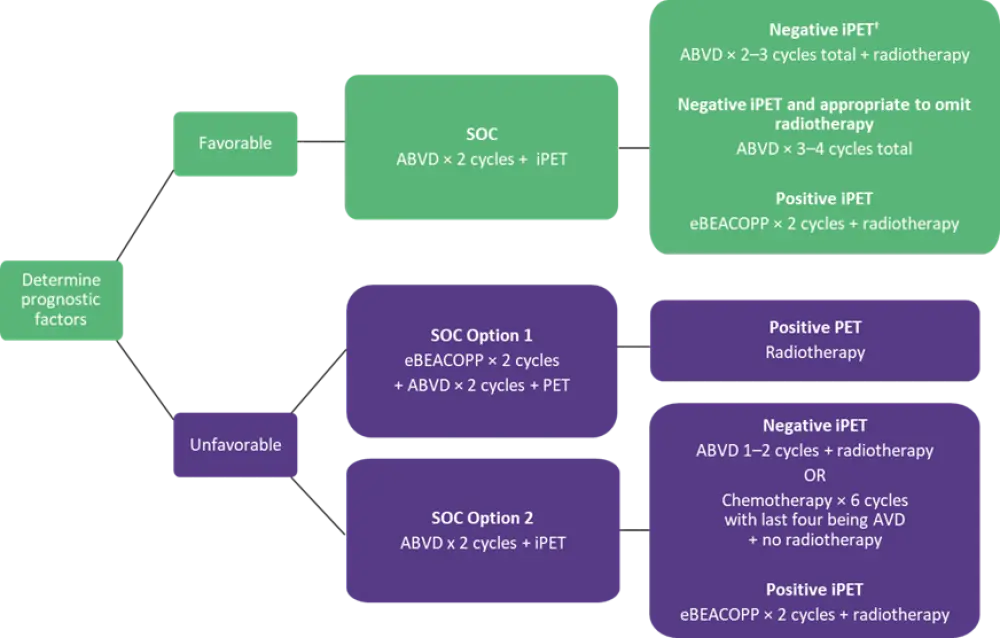

The recommendations for the management of early-stage favorable disease (Figure 1) are based on the evidence from three landmark studies UK-NCRI RAPID,2 EORTC/LYSA/FIL H10,3 and the GHSG HD164 trials.

- A negative interim PET (iPET) scan is internationally defined as a Deauville score (DS) of 1–3.

- Omitting radiotherapy may give certain patients longer-term benefits and these may vary depending on the age, sex, and pattern of disease in individual patients.

- To weigh up the risks and benefits of omitting radiotherapy, early discussion with a radiation oncologist within a multidisciplinary team is recommended.

- In iPET-negative patients where radiotherapy is omitted, a total of three or four cycles of doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine (ABVD) should be given. Six cycles of chemotherapy are not recommended in this low-risk group.

Early-stage unfavorable disease

In patients with early-stage unfavorable disease who achieve negative iPET, radiotherapy can be safely omitted with no risk to tumor control with an intensive initial chemotherapy approach. These patients can be started early on either escalated bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisolone (eBEACOPP) or ABVD (Figure 1).

- With the eBEACOPP approach, approximately 90% of patients are expected to achieve a negative iPET with an end-of-treatment PET scan and would avoid radiotherapy.

- With an ABVD approach, patients with a negative iPET should either be given a total of four cycles of ABVD followed by radiotherapy or a total of six cycles of chemotherapy with no radiotherapy.

- Positive iPET patients after two cycles of ABVD should be given dose-intensification of two cycles of eBEACOPP and radiotherapy.

Figure 1. Management of early-stage favorable and unfavorable disease*

ABVD, doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine; AVD, doxorubicin, vinblastine, dacarbazine; eBEACOPP, escalated bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisolone; iPET, interim positron emission tomography; PET, positron emission tomography; SOC, standard of care.

*Adapted from Follows et al.1

†Negative iPET defined as Deauville score 1–3.

Advanced-staged disease

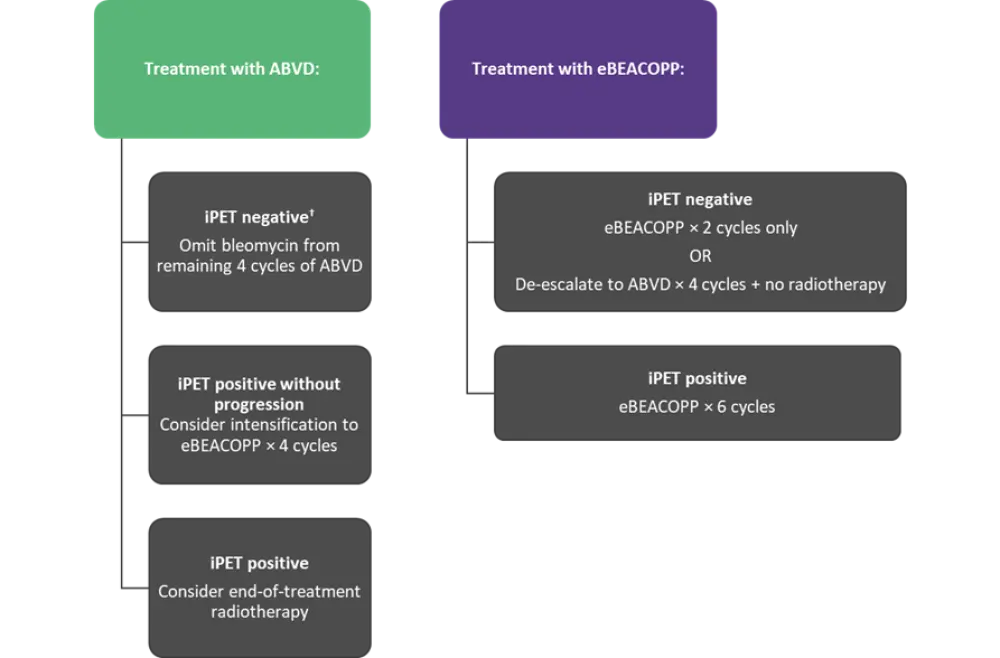

Initial treatment for adult patients aged ≤60 years with advanced stage cHL should comprise of either two cycles of ABVD or eBEACOPP followed by an iPET scan (Figure 2).

- Factors such as patient’s individual risk profile, and their opinion on toxicity/efficacy balance between regimens should be considered when choosing ABVD or eBEACOPP.

- In patients considered for treatment with eBEACOPP, procarbazine can be substituted for dacarbazine.

- Patients treated either with ABVD or eBEACOPP with a positive iPET should be considered for biopsy or interval scanning and/or radiotherapy.

- Patients developing progressive disease on therapy should be considered for treatment intensification with transplantation.

Figure 2. Management of advanced stage disease*

ABVD, doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine; eBEACOPP, escalated bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine and prednisolone; iPET, interim positron emission tomography; SOC, standard of care.

*Adapted from Follows et al.1

†Negative iPET defined as Deauville score 1–3.

Radiotherapy for cHL

The risk of relapse is reduced in early-stage patients treated with ABVD. The internationally recognized standard of care (SOC) for cHL treated with combined-modality therapy is involved-site radiotherapy (ISRT).

- For favorable early-stage disease, the GHSG ISRT dose should be 20 Gy

- For other indications, the ISRT dose should be 30 Gy and for partial responses a boost of 36–45 Gy may be considered

Patient’s individual risk profile, and balance between toxicity and efficacy should be considered in the decision about omitting radiotherapy.

PET in cHL

The use of PET is crucial in the management of cHL to augment staging and guide therapy. PET scan reports should always include a DS and metabolic response category for response assessment.

- DS 1, 2, and 3 should be considered as a complete metabolic response.

- End-of-treatment PET should be used in all iPET-positive patients to determine their response status.

- In patients with a DS of 4 or 5, biopsy or interval imaging is advised to confirm residual disease prior to second-line therapy.

- Standard iterative reconstruction, such as ordered-subset-expectation-maximisation (OSEM) is recommended.

Management of cHL in select populations

Teenagers and young adults

Treatment for teenagers and young adults (TYA) may be based on pediatric or adult protocols depending on the center expertise and balance between toxicity and efficacy, and consideration should be given to:

- Long-term risks of organ toxicity

- Secondary cancer

- Impact on fertility (referral to fertility specialist prior to treatment should always be offered, if timing permits)

Pregnancy

Pregnant patients with cHL should be jointly managed by a specialized obstetric/fetal medicine unit. Standard practice in this population would not be to delay initiation of chemotherapy. However, radiotherapy should be delayed until after delivery if possible.

- To reduce fetal radiation exposure, staging investigations and response evaluation should be tailored to clinical presentation with input from radiology.

- ABVD is the preferred treatment in this population unless contraindicated.

Elderly

The comorbidity assessment tool should be used to distinguish between ‘frail’ and ‘non-frail’ patients to establish their fitness to receive combination chemotherapy.

- ‘Frail’ patients should be offered chlorambucil, vinblastine, procarbazine, and prednisolone (ChlVPP), while ‘non-frail’ patients should be offered conventional anthracycline-based combination chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy with the aim of achieving complete remission.

- ‘Non-frail’ patients may be treated with ABVD; however, the use of bleomycin requires extreme caution and, therefore, doxorubicin, vinblastine, dacarbazine (AVD) is the preferred choice.

- ABVD may be limited to three cycles if PET negativity is achieved in elderly patients with early- and advanced-stage disease.

- Alternatives to anthracycline-containing regimens in specific elderly population may include either cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone (CHOP) and doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisolone (ACOPP).

Supportive and follow-up care

- Patients with cHL are at a significantly increased risk of early morbidity and mortality compared to the general population and, therefore, the following points after care should be considered:

- Patients should usually be followed-up for up to 2 years after first-line therapy and the ABVD cycle should not be delayed for neutropenia.

- Patients should be offered counselling regarding their increased risk of secondary cancers, and cardiovascular and pulmonary disease that may impact their lifestyle choices and on optimizing prenatal/ante-natal care where appropriate.

- Breast screening should be offered to women with radiotherapy under the age of 36 years, starting either 8 years after radiotherapy or at the age of 25 years, whichever is later.

- Patients treated with radiotherapy to the neck and upper mediastinum should be offered regular thyroid function tests.

- Patients should be offered follow-up discussions about impact on fertility treatment, menopausal status, and referral for specialist advice where appropriate.

- Patients should receive irradiated blood products for life.

Conclusion

Although cHL is a curable disease, the management of cHL has a significant impact on patients’ quality of life. This guideline on the first-line management of cHL provides an overview of the clinical management of adult patients with cHL. The guideline recommends iPET-guided therapy to reduce treatment-related morbidity and escalating or de-escalating approaches with ABVD and BEACOPP to prevent relapses. The guidance may not be appropriate for all patients with cHL and, therefore, also covers different populations where individual patient circumstances may dictate an alternative approach to their management.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content