All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the Lymphoma Coalition.

The lym Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the lym Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The lym and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Lymphoma & CLL Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by AbbVie, BeOne Medicines, Miltenyi Biomedicine, Nurix Therapeutics, Roche, Sobi, and Thermo Fisher Scientific and supported through educational grants from Bristol Myers Squibb, Lilly, and Pfizer. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View lymphoma & CLL content recommended for you

Predicting long-term cardiovascular risk in patients with early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma treated with involved field radiotherapy

For patients with early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma (ES-HL), the decision to assign either radiotherapy or no further treatment following chemotherapy requires balancing the risk of long-term cardiovascular toxicity with the potential for improved relapse-free and overall survival. Radiotherapy exposure has long been implicated as the leading cause of mortality among HL surivors.1 When compared with extended-field radiotherapy, which was used historically, involved field radiotherapy (IFRT) presents a less intensive approach that involves targeting only sites of disease. However, no data are available for the amount of radiation the heart is exposed to during IFRT and how this translates into mortality risk.

In a recent study by Cutter, et al. published in Journal of Clinical Oncology, the investigators aimed to quantify the cardiovascular radiation doses received by patients with ES-HL given IFRT and predict the 30-year cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk and incidence in patients from the UK National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) Lymphoma Study Group RAPID trial, who were either positron emission tomography (PET) negative or positive. We summarize key results below.1

Methods

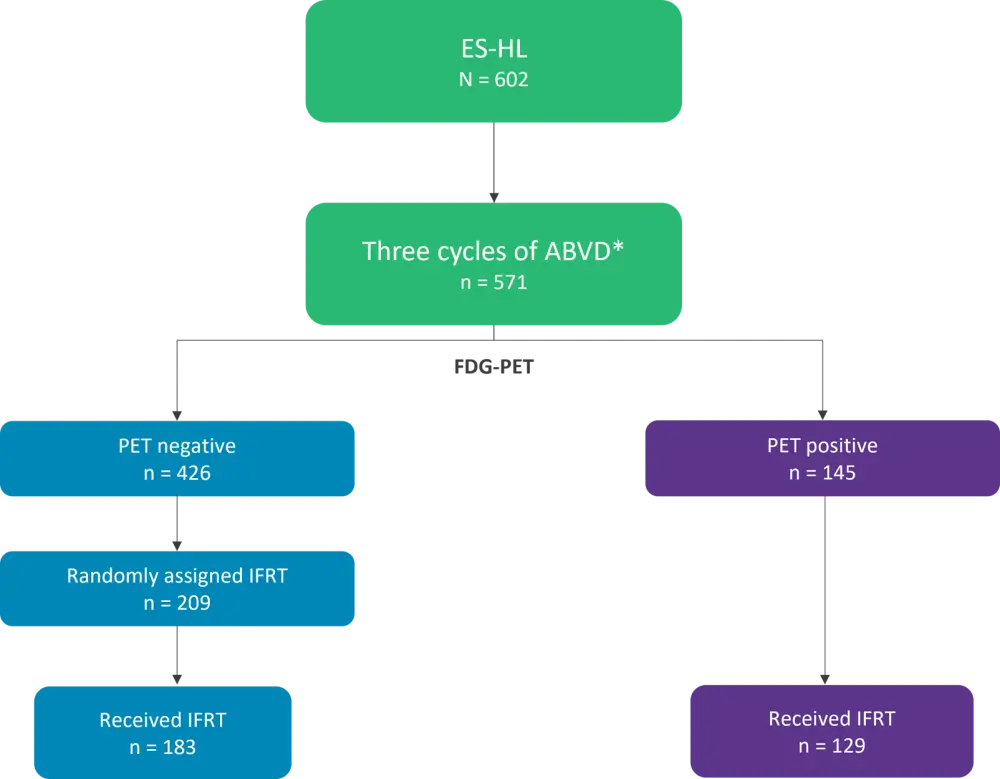

This was a retrospective analysis of patients enrolled in the UK NCRI RAPID trial between 2003 and 2010. The overall study design is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Study designⴕ

*ABVD, doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine; ES-HL, early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma; FDG-PET, Fluorodeoxyglucose-PET scan; IFRT, involved field radiotherapy; PET, positron emission tomography.

ⴕAdapted from Cutter, et al.1

Patients receiving IFRT were treated based on the extent of their disease as detected by computed tomography before chemotherapy. Computed tomography planning was used in 72% of patients, while x-ray simulation was used in 28%; original data sets and film copies, respectively, were used to estimate cardiovascular radiation dosimetry.

Predictions of 30-year cardiovascular mortality were based on the administered anthracycline dose and individual radiation doses to the

- whole heart;

- left ventricle;

- heart valves; and,

- common carotid arteries.

The predictions were derived using estimated percentage increases in mortality rate per unit dose, which were obtained from long-term studies of cardiac disease and stroke following HL treatment, combined with 5-year age- and sex-specific death rates from CVD in the general UK population. The 30-year risk of incident CVD was estimated similarly, using age- and sex-specific first CVD incidence rates from a representative UK cohort.

Cardiovascular doses

Sufficient data were available for 144 patients (78.7%) who were PET-negative and received IFRT, and 103 patients (79.8%) who were PET-positive and received IFRT.

Mean Heart Dose

- The average mean heart dose (MHD) for PET-negative patients was 4.0 Gy, and 69.4% of patients received <5 Gy.

- The most superior cardiac substructures, such as the pulmonary valve and sinoatrial node, received the highest mean radiation doses.

- A total of 73 patients had mediastinal involvement and received a significantly higher average MHD than patients without mediastinal involvement (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of radiation dose to cardiovascular strictures*

|

*Data from Ramroth, et al.1 |

||||||

|

Cardiovascular structure, Gy |

Mediastinal involvement |

No mediastinal involvement |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Average |

Range |

SD |

Average |

Range |

SD |

|

|

Whole heart |

7.8 |

0.8–24.0 |

5.4 |

0.3 |

0.1–1.4 |

0.2 |

|

Left coronary artery |

8.6 |

0.6–23.9 |

6.0 |

0.3 |

0.21–2.2 |

0.3 |

|

Right coronary artery |

7.3 |

0.5–27.9 |

6.5 |

0.2 |

0–0.7 |

0.2 |

|

Circumflex coronary artery |

12.4 |

0.8–32.5 |

9.1 |

0.4 |

0.1–2.4 |

0.4 |

|

Aortic valve |

16.1 |

0.9–34.0 |

11.2 |

0.5 |

0.1–1.5 |

0.3 |

|

Mitral valve |

8.7 |

0.6–32.7 |

9.7 |

0.3 |

0–1.8 |

0.3 |

|

Tricuspid valve |

6.2 |

0.4–31.9 |

8.0 |

0.2 |

0–0.7 |

0.2 |

|

Pulmonary valve |

22.3 |

1.8–34.5 |

9.2 |

0.7 |

0.1–2.6 |

0.5 |

|

Left ventricle |

3.3 |

0.3–20.5 |

3.9 |

0.2 |

0–2.1 |

0.3 |

|

Right ventricle |

4.8 |

0.4–26.9 |

5.5 |

0.2 |

0–1.0 |

0.2 |

|

Left atrium |

15.8 |

1.5–32.8 |

8.8 |

0.5 |

0.1–1.4 |

0.3 |

|

Right atrium |

9.9 |

0.8–27.7 |

8.1 |

0.3 |

0–1.1 |

0.2 |

|

Sinoatrial node |

21.7 |

1.3–34.9 |

9.9 |

0.6 |

0.1–2.2 |

0.4 |

|

Atrioventricular node |

8.8 |

0.6–32.0 |

10.5 |

0.3 |

0–0.9 |

0.2 |

|

Left carotid artery |

28.3 |

8.7–38.4 |

5.1 |

15.4 |

0.3–34.6 |

12.3 |

|

Right carotid artery |

28.2 |

12.2–37.8 |

5.0 |

14.3 |

0.7–30.7 |

10.8 |

Carotid Artery Dose

Overall, the mean dose to the carotid arteries was 21.5 Gy, though the range for carotid artery dose varied greatly (left: 0.3–38.4 Gy; right: 0.7–37.8) depending on whether the patient received unilateral or bilateral neck irradiation. Again, the mean dose was much higher for patients with mediastinal involvement compared with those without (Table 1). Dose distributions were similar in PET-positive patients receiving IFRT.

Predicted 30-year risks of cardiovascular related mortality

The average predicted 30-year cardiovascular mortality risk for PET-negative patients who received ABVD followed by IFRT was 5.02%. This comprised expected risk from general population rates (3.52%), absolute excess risk from anthracycline chemotherapy (0.94%), and absolute excess risk from IFRT (0.56%, most of which was attributed to ischemic heart disease and stroke). The predicted 30-year absolute excess was <0.5% in 67% of patients and >1% in 15% of patients, while the median risk was 0.26%; the range across individual patients was 0.01%–6.79%.

Mortality from heart disease

The average 30-year absolute excess risk for mortality from heart disease ranged from 0.03% for those receiving <5 Gy to 2.20% for those receiving ≥10 Gy (Individual range, 0.002%–6.55%).

The overall average was 0.42%, 0.79% for those with mediastinal involvement vs 0.05% for those without. Average MHD was higher for females than for males (5.4 vs 2.7 Gy) as a higher proportion of females had mediastinal involvement (59% vs 41%) and, on average, a lower inferior border to the mediastinal radiation field (which was the main determinant of MHD and thus of cardiac risk). As men have higher cardiac mortality rates in the general population, the estimated 30-year absolute excess mortality risk from treatment-related heart disease (chemotherapy and radiotherapy combined) was lower for females than for males (1.2% vs 1.5%).

Mortality from stroke

When determining mortality risk from stroke using mean bilateral carotid artery dose, the predicted 30-year average absolute excess radiation-related risk varied from 0.05% in those receiving <10 Gy to 0.24% in those receiving ≥30 Gy.

Predicted 30-year risks of incident CVD

The average 30-year predicted risk of CVD for PET-negative patients receiving IFRT after ABVD was 35.8%. This comprised expected risk from the general population (22.9%), absolute excess risk due to anthracycline chemotherapy (6.7%), and absolute excess risk due to IFRT (6.2%, most of which was attributed to ischemic heart disease and stroke). The predicted 30-year absolute excess risk was <5% in 58% of patients and >10% in 24% of patients, ranging from 0.31%–31.09% across individuals. The average predicted 30-year excess absolute radiation-related incidence risk for the 50% of PET-negative patients with the lowest predicted radiation-related cardiovascular risks would be 1.79%

Incidence of heart disease

The average predicted 30-year absolute excess risk of radiation-related heart disease when categorizing patients by MHD ranged from 0.21% for those receiving <0.5 Gy to 16.33% for those receiving ≥10 Gy. The radiation-related risk ranged from 0.03% to 27.88%. The average was 3.93%, 7.66% for those with mediastinal involvement and 0.31% without.

Incident risk of Stroke

The predicted 30-year absolute excess risk of incident stroke ranged from 0.66% in those receiving <10 Gy to 3.42% in those receiving ≥30 Gy, with a range of 0.09% to 5.35% and an average of 2.31%.

Conclusion

Analysis of PET-negative patients from the RAPID trial revealed that the risk of CVD related mortality and incidence was low for most of the cohort. As it is associated with improvements in relapse-free and overall survival, most patients should be able to receive IFRT, particularly with new techniques and lower radiation doses. A proportional increase in excess risk was associated with mediastinal involvement and higher dosage. As such, individual diagnosis that identifies patients with such characteristics may help guide treatment decisions.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content