All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the Lymphoma Coalition.

The lym Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the lym Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The lym and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Lymphoma & CLL Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by AbbVie, BeOne Medicines, Johnson & Johnson, Miltenyi Biomedicine, Nurix Therapeutics, Roche, Sobi, and Thermo Fisher Scientific and supported through educational grants from Bristol Myers Squibb, Lilly, and Pfizer. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View lymphoma & CLL content recommended for you

Efficacy and safety of CD22/CD19 dual-targeted CAR T-cell therapy in B-cell malignancies

Do you know... In the pooled safety analysis of ALL and NHL studies, which of the following types of CAR T-cell therapy was associated with a significantly higher incidence of cytokine release syndrome?

Despite the high efficacy of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy in relapsed/refractory (R/R) B-cell malignancies such as acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), around 30–50% of relapses are predominantly due to CD19 antigen loss and lack of CAR T-cell persistence.1

CD22 represents a different target antigen for CAR T-cells as it is widely expressed in most B-cell malignancies. CD22-directed CAR T-cell therapy has yielded a complete remission (CR) of 73% and a median remission duration of 6 months in patients with negative CD19-antigen expression who previously received CD19 CAR T-cell therapy, though treatment failure is mainly due to a reduced CDD-antigen density at relapse.1

Some studies on the treatment of solid tumors have shown that dual-antigen targeting can result in synergistic responses and prevent relapse compared with single-antigen target therapy. However, there are limited data on the efficacy and safety of dual-targeted CD22/CD19 CAR T-cell therapy in B-cell malignancies.1

The Lymphoma Hub previously reported key updates on dual targeted CAR T-cell therapies for different types of lymphomas. Here, we summarize the article by Nguyen et al.1 published in Cancer Medicine on the efficacy and safety of dual-targeted CD22/CD19 CAR T-cell therapy in B-cell malignancies, including B-cell ALL and NHL.

Study methods

This is a meta-analysis that included prospective, retrospective, observational, and interventional clinical studies as well as conference abstracts in a systematic review of qualitative analysis and case series. Patients of all ages, genders, and ethnicities with any R/R B-cell hematological malignancies who received CD22/CD19 dual-targeting CAR T-cell therapy, both alone or in combination with other treatments, were included. All CAR Ts used were either second- or next-generation.

Primary endpoints

- Overall response (OR), defined as the sum of CR and partial response (PR)

- Complete response, defined as the absence of detectable cancer in B-ALL, as <5% bone marrow blasts by morphology

Secondary endpoints

- PR, defined as a response to treatment that does not meet the criteria for CR

- Minimal residual disease (MRD) response, defined as bone marrow blast proportion <10−4 by multiparameter flow cytometry or real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- Overall survival (OS), defined as the time from the start of therapy until death from any cause

- Progression-free survival (PFS), defined as time from the start of therapy until disease progression

- Safety

Results

Of the 994 articles identified, 14 studies were included in the quantitative meta-analysis, all of which were published between 2019 and 2022 and conducted across the UK, USA, and China. In total, 405 patients were enrolled: 120 with ALL and 285 with NHL.

Among the seven ALL studies included (Table 1), all patients were treated with CD22/CD19 dual-targeting CAR T-cell therapy alone, five of which originated from autologous transduced T-cells and two from allogeneic T-cells. 47.5% of patients were pretreated with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Response was measured at Day 28 in five studies, and at Day 60 and Day 90 in two other studies.

Across the eight NHL studies (Table 2), 221 out of 285 patients had diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Patients received either dual-targeting CAR T-cell monotherapy alone or combined with other treatments. 11.9% of patients were pretreated with HSCT with a median follow-up of 14.1 months. The response was measured at Month 1 in four trials and Month 3 in the other four trials.

Table 1. Studies on CD22/CD19 dual-targeting CAR T-cell therapy in R/R ALL*

|

ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor. *Data from Nguyen, et al.1 |

|||

|

CAR T-cell product & patient population (n) |

Patient age (range), years |

Prior therapies, |

Infused CAR T-cell dose |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Bicistronic vector (n = 15) |

8 (4–16) |

2 (1–4) |

0.3 to 5 × 106 CD19/22 CAR T-cells/kg |

|

Tandem CAR (n = 6) |

28 (17–44) |

2 (1–3) |

1.7 to 3 × 106 CD19/22 CAR T-cells/kg |

|

Tandem CAR (n = 6) |

49 (26–56) |

5 (2–8) |

1−3 × 106 CD19/22 CAR T-cells/kg |

|

Coadministration of CD19- and CD22-targeted CAR T-cells (n = 21) |

21 (1.6–55) |

>2 |

0.486 to 5.0 × 105 CD19 CAR T-cells/kg and 0.32 to 5.0 × 105 CD22 CAR T-cells/kg |

|

Tandem CAR (n = 17) |

47 (26–68) |

>2 |

1 to 3 × 106 CD19/22 CAR T-cells/kg |

|

Coadministration of CD19- and CD22-targeted CAR T-cells (n = 51) |

27 (9–62) |

2.5 (2–4) |

2.6±1.5 × 106 CD19 CAR T-cells/kg and 2.7±1.2 × 106 CD22 CAR T-cells/kg |

|

Coadministration of CD19- and CD22-targeted CAR T-cells (n = 4) |

28 (18–40) |

3.5 (2–4) |

1 × 106 CD22 CAR T-cells/kg and 1 × 106/kg CD19 CAR T-cells/kg |

Table 2. Studies on CD22/CD19 dual-targeting CAR T-cell therapy in R/R NHL*

|

B-LBL, B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; FL, follicular lymphoma; HGBL, high-grade B-cell lymphoma; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; GCB, germinal center B-cell like; ILBCL, intravascular large B-cell lymphoma; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; NHL, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; non-GCB, non-germinal center B-cell like; NOS, not otherwise specified; NR, not reported; PMBCL, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma; TFL, transformed follicular lymphoma. |

||||

|

CAR T product & patient population (n) |

Disease type |

Patient age (range), years |

Prior therapies, n (range) |

Infused CAR T-cell dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Coadministration of CD19- and CD22-targeted CAR T-cells + HSCT (n = 42) |

DLBCL (n = 30) |

41 (24–61) |

4 (2–5) |

1.0 to 10.0 × 106 CD22 CAR T-cells/kg and 1.8 to 10.0 × 106 CD19 CAR T-cells/kg |

|

Tandem CAR (n = 21) |

DLBCL (n = 14) |

69 (25–78) |

3.1 (2–7) |

1 to 3 × 106 CD19/22 CAR T-cells/kg |

|

Tandem CAR (n = 16) |

Non-GCB DLBCL (n = 10) |

52.5 (23–68) |

2.9 (2–4) |

4.9–9.4 × 106 cells CD19/ CD22 CAR T-cells/kg |

|

Coadministration of CD19- and CD22-targeted CAR T-cells + HSCT in trial B (n = 123) |

DLBCL NOS (n = 86) |

44 (17–69) |

3.2 (2–4) |

Trial A: 4.1 (1.4– 8.9) × 106 CD19 CAR T-cells/kg and 6.0 (1.0– 11.4) × 106 CD22 CAR T |

|

Coadministration of CD19- and CD22-targeted CAR T-cells (n = 13) |

Non-GCB DLBCL (n = 9) |

42 (23–65) |

3.1 (2–6) |

4.1 (2.6–8.4) × 106 CD22 CAR T-cells/kg and 4.3 (2.0–9.2) × 106 for CD19 CAR T-cells/ |

|

Coadministration of CD19- and CD22-targeted CAR T-cells + HSCT (n = 14) |

DLBCL (n = 12) |

47.5 (28–66) |

4.5 (2–6) |

5.6 (2.9–11.0) × 106 CD22 CAR T-cells/kg and 4 (2.1–8.0) × 106 CD19 CAR T-cells/kg |

|

Tandem CAR (n = 32) |

DLBCL (n = 17) |

<60: 24 |

>2 |

3.69 × 108 to 3.28×109 CD19/22 CAR T-cells |

|

NR (n = 24) |

DLBCL (n = 20) |

51 (26–70) |

2 (1–5) |

NR |

Efficacy

Overall, 119 patients across the seven ALL clinical trials were evaluable for responses:

- The pooled OR and CR rates were 97% and 93%, respectively.

- Of the 117 MRD-evaluable patients, 109 (93%) achieved an MRD-negative CR.

- Of the 48 patients in the survival analysis, the 6-month OS and PFS were 83% and 50%, respectively.

- The pooled 1-year OS and PFS were 70% and 49%, respectively.

For NHL, a total of 281 patients across the eight studies were evaluable for response:

- The pooled OR and CR rates were 85% and 57%, respectively

- Of the 145 patients in the survival analysis, the 12-months OS and PFS were 77% and 56%, respectively.

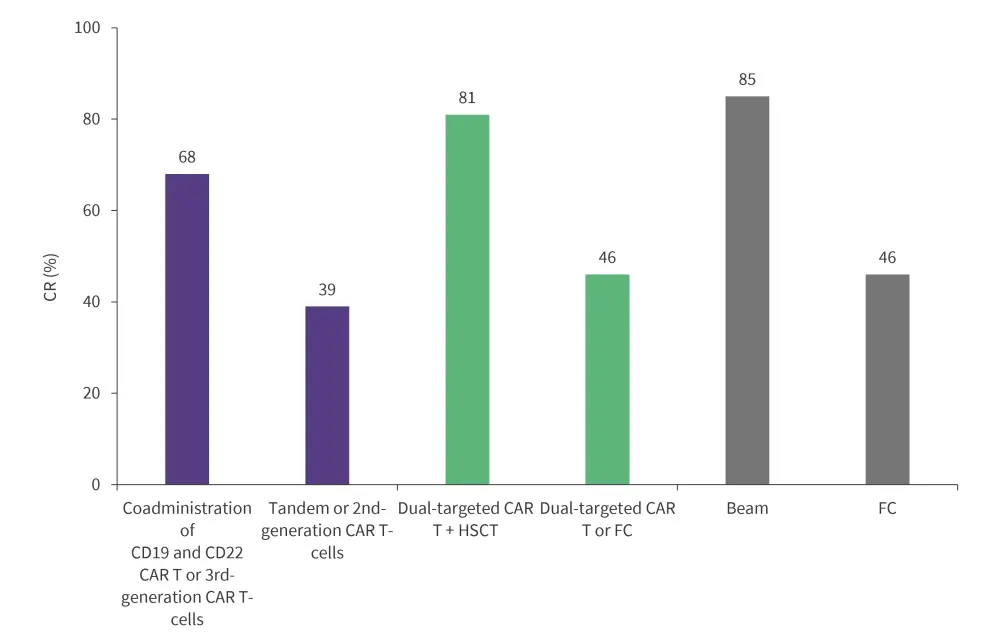

- Significant heterogeneity in CR was observed among patients in the subgroup analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1. CR across dual-targeted approach, CAR T generation, and lymphodepletion regimen in NHL studies*†

BEAM, carmustine, etoposide, ara-cytarabine, melphalan; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CR, complete remission; FC, fludarabine and cyclophosphamide; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

*Data from Nguyen, et al.1

†p < 0.01 for the difference in lymphodepletion regimen and combination versus dual-targeting CAR T-cell therapy alone.

Safety

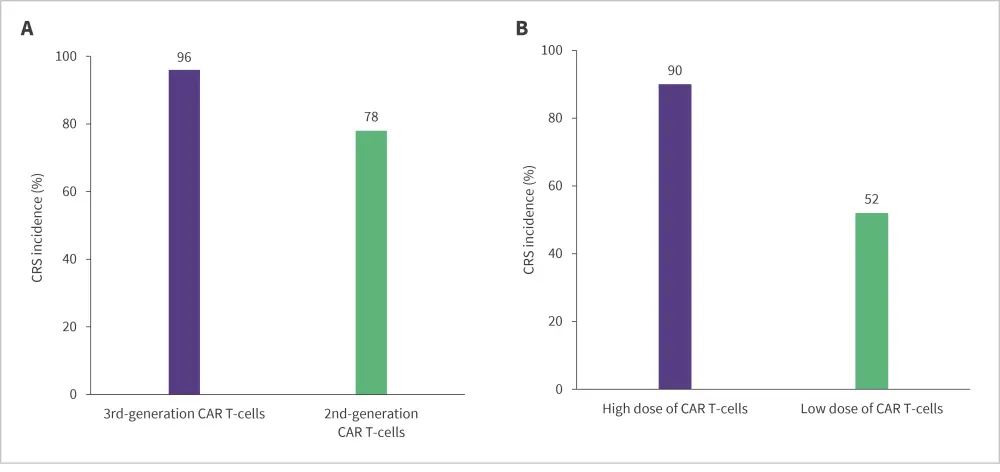

All patients were included in the safety analysis. Of the 120 patients with ALL, 86% experienced a cytokine release syndrome (CRS) event (7% severe CRS). Neurotoxicity occurred in 12% of patients. Studies using a second-generation dual-targeted CAR T-cell therapy reported a significantly lower pooled CRS compared with those using third-generation CAR T-cell therapy (p = 0.04). Moreover, clinical trials that used a higher dose of CAR T-cells reported a significantly higher percentage of CRS compared with those using a lower dose of CAR T-cells (p < 0.01) (Figure 2).

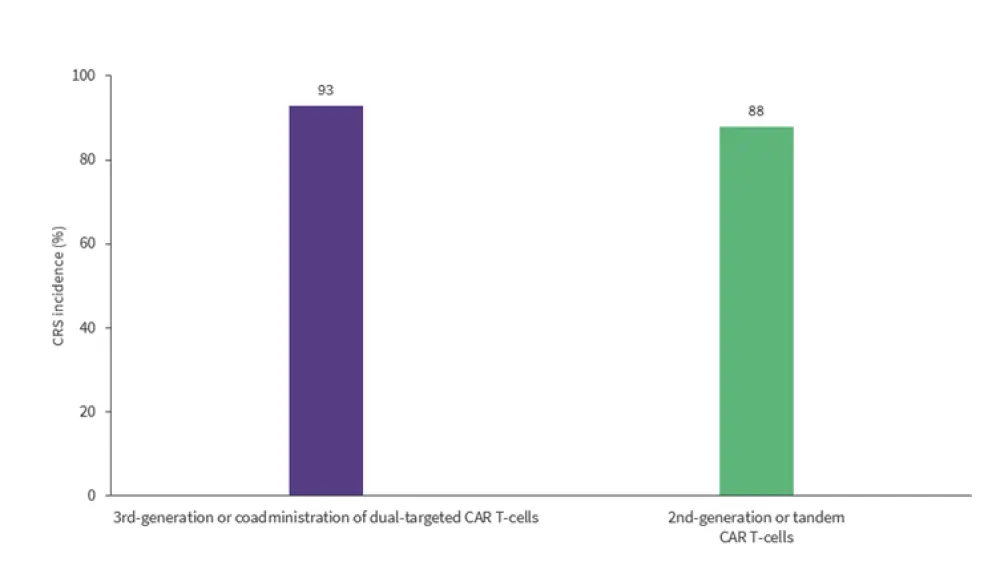

In the NHL studies, 89% of patients experienced any-grade CRS and 12% developed severe CRS. Additionally, immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome was reported in 11% of patients. Similar to ALL studies, third-generation CAR T-cells or coadministration of dual-targeted CAR T-cell therapy reported a significantly higher rate of CRS compared with second-generation or tandem CAR T-cells (p < 0.01) (Figure 3).

Figure 2. CRS incidence by CAR T generation and dose in ALL studies*

CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CRS, cytokine release syndrome.

*Data from Nguyen, et al.1

Figure 3. CRS incidence by generation and type of dual-targeted CAR T-cell therapy in NHL studies*

CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CR, complete remission; CRS, cytokine release syndrome.

*Data from Nguyen, et al.1

Conclusion

Despite the small sample sizes and single-arm trials, this meta-analysis showed the clinical effectiveness and tolerable safety profile of CD22/CD19 dual-targeted CAR T-cell therapy with high responses observed across all ages, genders and ethnicity. Subgroup analyses revealed that third-generation CAR Ts yielded higher responses than second generation; and safety analyses showed that third-generation CAR Ts were associated with a higher incidence of CRS compared with second-generation CAR Ts in patients with both ALL and NHL.

Further clinical studies investigating alterations of CAR structure, and different therapy modalities including combination treatment, patient selection, and specific lymphodepletion are warranted to understand the efficacy and safety of dual-targeted CAR T-cell therapy.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content