All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the Lymphoma Coalition.

The lym Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the lym Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The lym and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Lymphoma & CLL Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by AbbVie, BeOne Medicines, Johnson & Johnson, Miltenyi Biomedicine, Nurix Therapeutics, Roche, Sobi, and Thermo Fisher Scientific and supported through educational grants from Bristol Myers Squibb, Lilly, and Pfizer. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View lymphoma & CLL content recommended for you

Phase III BELINDA: tisa-cel vs standard of care as second line treatment of aggressive B-cell lymphoma

The prognosis for relapsed or refractory aggressive B-cell lymphoma is poor, particularly in those who relapse within the first year of receiving first-line treatment. The current standard of care for these patients—at least those who are suitable for further treatment—is a platinum-based chemotherapy regimen followed by autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), though in more than half of these patients, chemotherapy is unable to sufficiently reduce tumor burden, making them ineligible for transplantation.1

Based on the clear unmet need in this patient population, the phase II JULIET trial was conducted to investigate tisagenlecleucel (tisa-cel), a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, in the second line setting for patients with relapsed or refractory DLBCL who were ineligible for or had disease progression following autologous HSCT. The positive results from JULIET—a best overall response rate of 52%, with 40% achieving complete response—led to further investigation of tisa-cel vs standard of care in the phase III randomized BELINDA trial.1,2

Results from BELINDA were presented by lead investigator Michael Bishop at the 63rd American Society of Hematology (ASH) Annual Meeting and Exposition in December 2021 as part of the late-breaking abstracts session, with the full study manuscript having been published hours prior in the New England Journal of Medicine. While the results (detailed below) have been characterized by some as “negative,” largely in light of the results of other CAR T-cell studies presented at ASH, BELINDA represents a landmark study that offers many important takeaways, particularly regarding trial design.

Study design

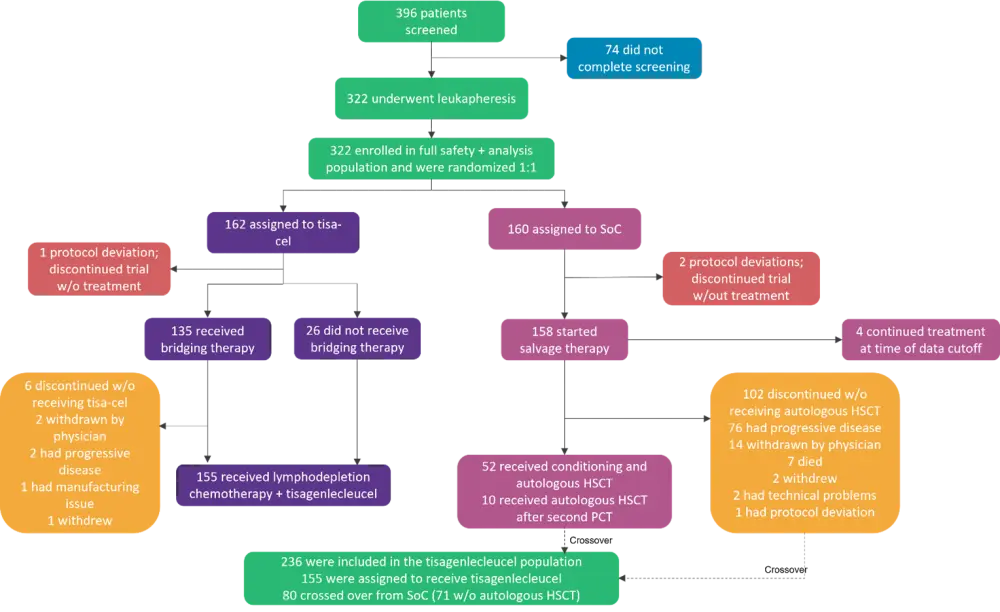

BELINDA was an international, randomized, phase III clinical trial comparing tisa-cel to current standard of care second-line treatment strategies in DLBCL (Figure 1). Patients underwent leukapheresis and were randomized 1:1 to:

- Tisa-cel, which consisted of optional bridging therapy with investigator’s choice of four prespecified platinum-containing chemotherapy regimens, lymphodepletion with fludarabine + cyclophosphamide (or bendamustine), and a single infusion of tisa-cel.

- Standard of care, which consisted of investigator’s choice of four prespecified chemotherapy regimens; patients having a response went on to receive high-dose chemotherapy and autologous HSCT.

Eligibility criteria included:

- Patients aged ≥18 years.

- Histologically confirmed aggressive B-cell lymphoma that was refractory or relapsed within 12 months of the last dose of first-line therapy with an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody + anthracycline-based chemotherapy.

- Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status (PS) score of 0 or 1 and adequate organ function.

- Eligibility for autologous HSCT according to investigator’s assessment.

Figure 1. Randomization and treatment*

HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; PCT, platinum-based immunochemotherapy; Soc, standard of care; tisa-cel, tisagenlecleucel.

*Adapted from Bishop, et al.1

Secondary endpoints included:

- Overall survival (OS), which was to be formally tested only if the EFS results were statistically significant;

- percentage of patients with a response;

- safety; and

- cellular kinetics.

Baseline characteristics

Of the 396 patients who were screened, 322 underwent randomization. All screened patients underwent leukapheresis for lymphocyte collection due to the crossover design of the trial. Due to the transplant eligibility requirement, most patients were under 65 years of age. Patient characteristics are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Baseline patient demographics and clinical characteristics*

|

ABC, activated B cell; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; GCB, germinal center B cell; IPI, International Prognostic Index; IQR, interquartile range; NOS, not otherwise specified; SoC, standard of care; tisa-cel, tisagenlecleucel. |

||

|

Characteristic, % (unless otherwise specified) |

Tisa-cel group (n = 162) |

SoC group (n = 160) |

|---|---|---|

|

Median age (range), years |

59.5 (19–79) |

58 (19‒77) |

|

Age ≥65 |

33.3 |

28.8 |

|

Male sex |

63.6 |

61.2 |

|

Race |

||

|

White |

79.0 |

80.0 |

|

Asian |

12.3 |

13.8 |

|

Black |

4.9 |

1.9 |

|

Other/unknown |

3.7 |

4.4 |

|

Hispanic or Latino ethnic group |

7.4 |

8.1 |

|

Geographic region |

||

|

United States |

29.6 |

29.4 |

|

Non-United States |

70.4 |

70.6 |

|

ECOG Performance Score of 1 |

43.2 |

40.6 |

|

IPI score ≥2 |

65.4 |

57.5 |

|

Disease subtype |

||

|

DLBCL, NOS |

62.3 |

70.0 |

|

GCB-cell-like |

28.4 |

39.4 |

|

ABC-cell-like |

32.1 |

26.2 |

|

Unclassified/missing |

1.9 |

4.4 |

|

High-grade B-cell lymphoma with MYC |

19.8 |

11.9 |

|

Primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma |

7.4 |

8.1 |

|

High-grade B-cell lymphoma, NOS |

4.3 |

5.0 |

|

Follicular lymphoma grade 3B |

3.1 |

0.6 |

|

Other |

3.1 |

4.4 |

|

Transformation from previous lymphoma |

16.7 |

13.8 |

|

Remission duration |

||

|

Disease that was refractory to first-line |

66.0 |

66.9 |

|

Relapse <6 months after last dose of first |

18.5 |

20.0 |

|

Relapse 6–12 months after last dose of |

15.4 |

13.1 |

|

Median time since initial diagnosis (IQR), months |

8.4 (6.8‒11.1) |

8.2 (5.9‒11.4) |

|

Median time since most recent relapse or progressive disease (IQR), months |

1.4 (0.9‒2.2) |

1.1 (0.8‒1.8) |

|

One previous line of therapy for current lymphoma |

98.8 |

98.8 |

|

Disease stage at time of trial entry |

||

|

I or IE |

11.7 |

13.8 |

|

II, IIE, or II bulky |

22.2 |

25.0 |

|

III |

17.9 |

15.0 |

|

IV |

48.1 |

46.2 |

Results

CAR T-cell therapy manufacturing and time to infusion

The median times for manufacturing, shipment, and infusion for U.S. and non-U.S. patients are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Tisa-cel manufacturing and time to infusion

|

Median time point (range), days |

Overall |

U.S. patients |

Non-U.S. |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Time from leukapheresis to infusion |

52 (31‒135) |

41 (31‒91) |

57 (38‒135) |

|

Patients who received no |

44 (34‒76) |

— |

— |

|

Patients who received 1 cycle of |

47 (31‒79) |

— |

— |

|

Patients who received ≥2 cycles or |

58 (37‒135) |

— |

— |

|

Randomization to receipt of leukapheresis at manufacturing facility |

— |

6 (2‒12) |

10 (3‒27) |

|

Leukapheresis receipt at facility to tisa-cel shipment |

— |

23.5 (22‒34) |

28 (22‒115) |

|

Shipment to infusion |

— |

11 (4‒63) |

15 (2‒91) |

Receipt of treatment

- 95.7% of patients assigned to the tisa-cel group received tisa-cel at a median dose of 2.9 × 108 cells (range, 0.4‒5.9 × 108).

- 96.9% of patients in the standard of care group received at least two cycles of chemotherapy, and 53.8% received at least two regimens.

- 32.5% of patients in the standard of care group received autologous HSCT, of which 31% received 2 different chemotherapy regimens prior to HSCT.

- The median time from randomization to transplant was 3.0 months (range, 2.0‒5.2 months).

- Overall, 15.6% of patients became ineligible for transplantation during the treatment period for reasons other than inadequate response.

- At data cutoff, 50.6% of patients in the standard of care group had crossed over and received tisa-cel (10 patients crossed over from autologous HSCT).

- The median time from randomization to crossover infusion was 4.3 months (range, 2.5‒10.8 months).

Efficacy

EFS was not significantly different between the tisa-cel and standard of care groups (hazard ratio [HR], 1.07; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.82–1.40, two-sided p = 0.61); the median EFS for both groups was 3.0 months (Table 2). Median time from randomization to data cutoff was 10.0 months (range, 2.9‒23.2 months). Response rates for both groups are shown in Table 3.

EFS and OS were shorter among patients with high-grade B-cell lymphoma in both groups compared with patients with primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma or DLBCL.

Table 3. Overall response at Week 6 and best overall response*

|

CI, confidence interval; SoC, standard of care; tisa-cel, tisagenlecleucel. *Adapted from Bishop, et al.1 |

||||

|

Response†, % |

Week 5 assessment |

Best overall response at or after Week 12 assessment |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Tisa-cel |

SoC (n = 160) |

Tisa-cel |

SoC (n = 160) |

|

Best overall response |

||||

|

Complete |

11.1 |

19.4 |

28.4 |

27.5 |

|

Partial response |

27.2 |

34.4 |

17.9 |

15.0 |

|

Stable disease |

29.6 |

28.8 |

11.7 |

13.8 |

|

Progressive |

25.9 |

13.8 |

30.9 |

28.8 |

|

Unknown‡ |

6.2 |

3.8 |

11.1 |

15.0 |

|

Complete or partial response |

||||

|

Number of |

62 |

86 |

75 |

68 |

|

Percent (95% CI) |

38.3 (30.8‒46.2) |

53.8 (45.7‒61.7) |

46.3 (38.4‒54.3) |

42.5 (34.7‒50.6) |

In the tisa-cel group, responses occurred prior to CAR T-cell therapy infusion in 26.1% of U.S. patients and 46.3 of non-U.S. patients; additionally, six patients in the tisa-cel group had a response to CAR T-cell therapy but were recorded as having an event due to either stable disease or progression before or soon after infusion.

Safety

Almost all patients had an adverse event (AE) during the safety period (98.8% in each group).

- Grade ≥3 AEs occurred in 84.0% (n = 136) of patients in the tisa-cel group and 90.0% (n = 144) of patients in the standard of care group.

- Grade ≥3 treatment-related AEs occurred in 74.7% (n = 121) and 85.6% (n = 137) of patients in the tisa-cel and standard of care groups, respectively.

In the tisa-cel group:

- 61.3% (95/155) of patients who received an infusion had cytokine release syndrome (CRS), with 5.2% Grade ≥3.

- Median time to onset of CRS was 4 days (range, 1‒27 days) and median time to resolution was 5 days.

- 10.3% had neurologic AEs, with 1.9% Grade ≥3.

- Median time to onset was 5 days (range, 3‒93 days) and median time to resolution was 9 days.

Excluding CRS in the tisa-cel group, the most common AEs in both treatment groups were anemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and nausea.

In total, 32.1% (n = 52) of patients in the tisa-cel group and 28.1% (n = 45) of patients in the standard of care group died during the trial, with 25.9% (n = 42) and 20.0% (n = 32), respectively, due to disease progression. Ten patients in the tisa-cel group and 13 patients in the standard of care group died from AEs. Two patients in each group died due to SARS-CoV-2-related complications.

Tisa-cel expansion and persistence

In patients with a response to tisa-cel, the mean in vivo peak expansion was twice as high as in those without a response (median time to peak expansion was similar in both groups). Longer EFS was seen in patients with peak expansion that was higher than the median. At 4 months post-randomization, tisa-cel transgene was detected in 53 of the 54 samples that could be evaluated. Eighteen of the 38 patients who relapsed after having a response to tisa-cel had quantifiable transgene levels in the peripheral blood; in the remaining 20 patients, four had insufficient cellular kinetic data and 16 had had undetectable transgene levels.

Conclusion

While BELINDA did not demonstrate an EFS benefit with tisa-cel over standard of care, there is much to learn from—and consider with—this trial. Notably, the tisa-cel arm had a higher percentage of patients with progressive disease at Week 6 (prior to infusion) compared with the standard of care arm (25.9% vs 13.8%). The post hoc exploratory analyses conducted by the investigators suggested that pre-infusion disease burden impacts long-term outcomes with CAR T-cell therapy, which has been supported by evidence from ZUMA-1.3

Due to the enrollment of patients with high-risk, aggressive disease (and considering time to infusion), bridging therapy was allowed. The original definition of EFS was confounded by longer time to infusion and delayed response, as some events at the Week 12 assessment were observed before onset of treatment response. Time to infusion was prolonged due to pandemic-related logistical challenges affecting the transport of leukapheresis materials to and tisa-cel products from the manufacturing facility, which resulted in patients not meeting pre-infusion criteria at the time of tisa-cel availability and the need to delay infusion to allow for washout following bridging therapy.

Patients in the standard of care group were allowed to receive a second chemotherapy regimen, which improved efficacy in this group. While 53.8% of patients in the standard of care group received ≥2 salvage chemotherapy regimens, only 19% were eligible for autologous HSCT, highlighting the aggressive disease in this population. Despite this, the patients who received autologous HSCT contributed to the improved outcomes in the standard of care group.

These findings underline the importance of disease control prior to CAR T-cell infusion as well as the impact that time to infusion has on outcomes, and further research is necessary to investigate the effect of disease burden (and the potential for increasing cell dose) and prior therapies on CAR T-cell therapy response.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content