All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the Lymphoma Coalition.

The lym Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the lym Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The lym and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Lymphoma & CLL Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by AbbVie, BeOne Medicines, Johnson & Johnson, Miltenyi Biomedicine, Nurix Therapeutics, Roche, Sobi, and Thermo Fisher Scientific and supported through educational grants from Bristol Myers Squibb, Lilly, and Pfizer. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View lymphoma & CLL content recommended for you

Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia: An overview

Do you know... Which of the following mutations are most commonly associated with Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia?

Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia (WM) is a rare type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, accounting for 1–2% of all hematologic malignancies, and primarily affects the elderly.1,2 It presents as an accumulation of lymphoplasmacytic cells and the overproduction of monoclonal immunoglobulin M (IgM) proteins affecting the clinical sequelae.2 Due to this, it is a complex disease affecting multiple organs.2

Etiology3

To date, the cause of WM is unknown. Research is ongoing to investigate mutations potentially causing B-lymphocyte cells to divide and multiply uncontrollably and overwhelm the production of healthy blood cells. The two mutations are:

- MYD88, mutated in ~90% of patients with WM; and

- CXCR4, mutated in up to ~40% of patients with WM.

Although the cause remains unknown, several risk factors have been linked to the development of WM, including:

- previously diagnosed with IgM monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance or an autoimmune disease, such as Sjogren’s syndrome; or a viral illness, such as hepatitis C; and

- closely related family members with WM or lymphoma are at higher risk than patients with no genetic relation.

Epidemiology

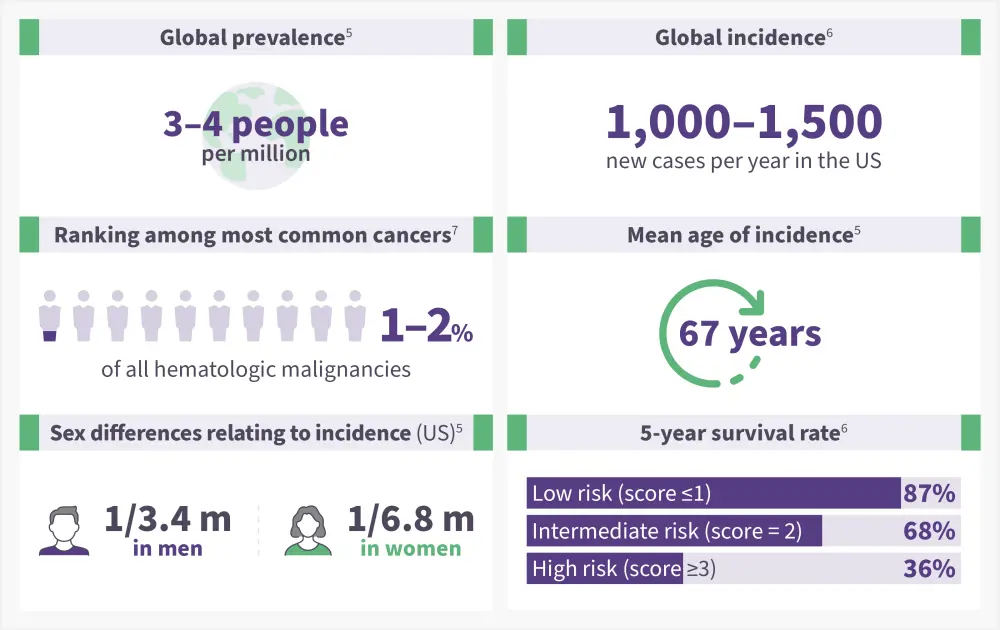

WM is a cancer that3,4:

- occurs in the elderly population, with a median age at diagnosis of ≥65 years;

- is more common in males than females; and

- varies in incidence by race and geographic location (higher among Caucasians compared with African Americans).

Figure 1. Epidemiology of WM*

WM, Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia; m, million.

*Data from NORD.5; Kaseb, et al.6; Stone and Pascual.7

Pathophysiology

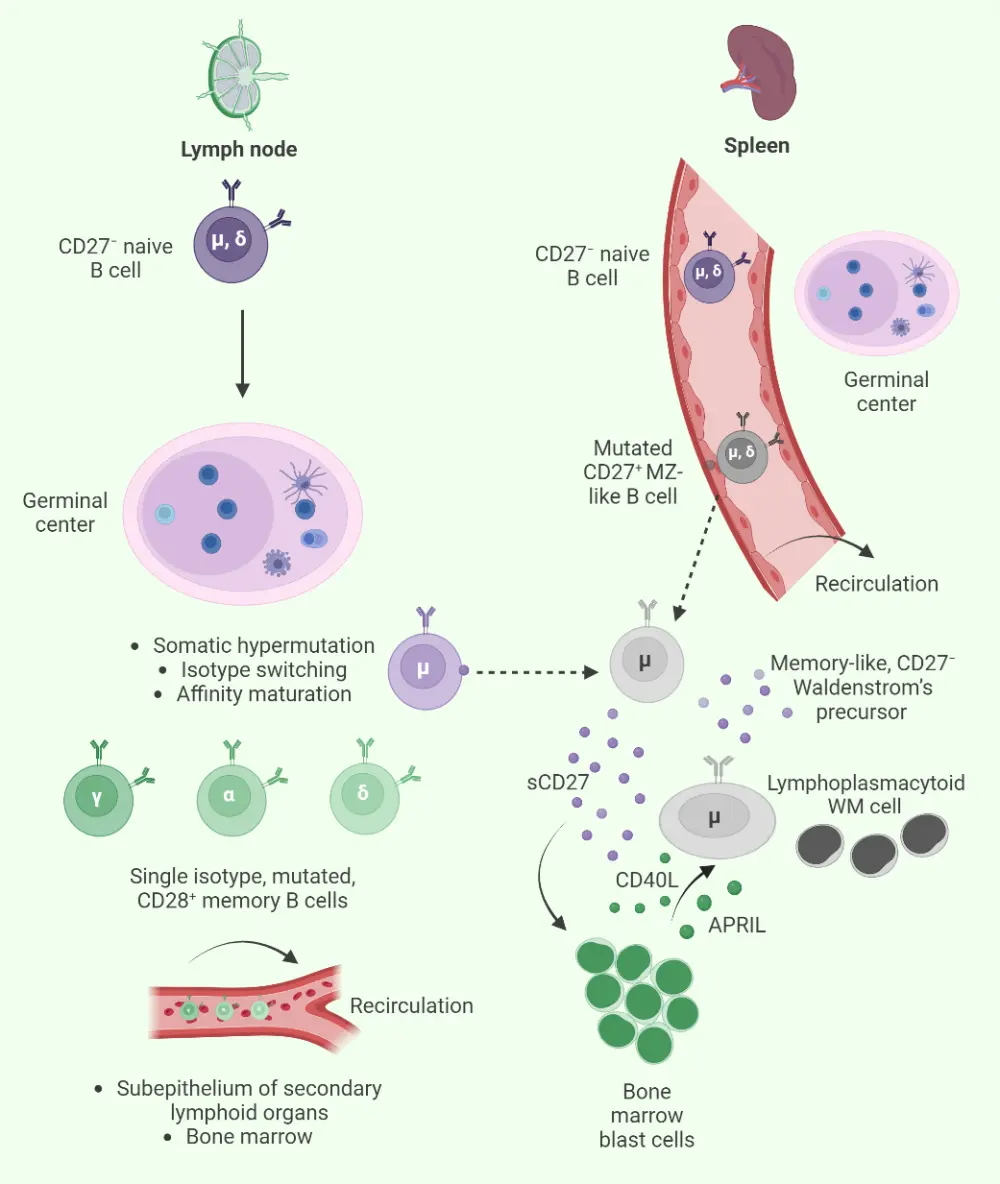

WM develops when lymphoplasmacytic cells become abnormal and secrete an excess of IgM protein.4 The pathophysiology of WM involves the presence of infiltrated lymphoplasmacytic cells in the bone marrow, spleen, lymph nodes, and liver among other sites (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Pathophysiology of WM*

WM, Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia.

*Adapted from Stone and Pascual.7 Created with BioRender.com

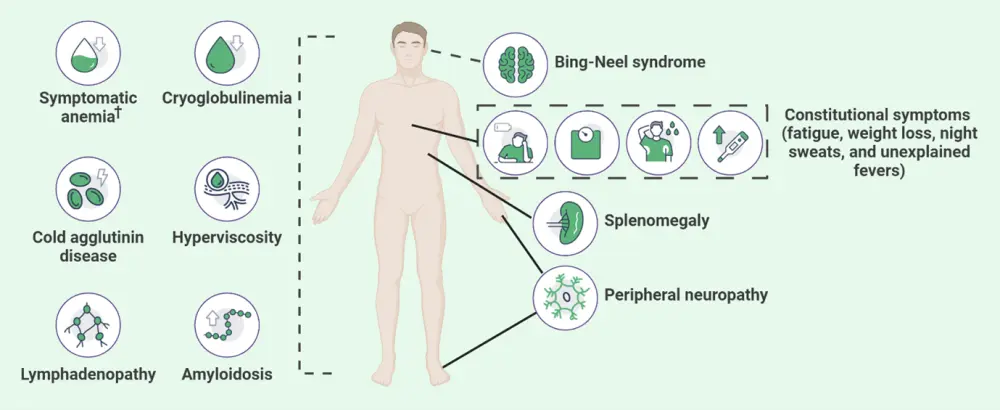

Signs and symptoms4

Not all patients with WM are symptomatic, with one in four reported as asymptomatic when diagnosed. WM is often discovered when a blood test is carried out for another cause or, after several years when symptoms begin to develop. Common symptoms reported early in diagnosis include weakness and fatigue due to anemia, as presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. WM signs and symptoms*

WM, Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia.

*Adapted from Sarosiek and Castillo.4 Created with BioRender.com.

Diagnosis

To confirm diagnosis, there must be a presence of a monoclonal IgM paraprotein and a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate in the bone marrow.3 WM can be diagnosed by4:

- Serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation to detect IgM presence

- Clonal infiltration of the bone marrow can be detected by positive expression of surface IgM, CD19, CD20, CD25, and CD27

- Bone marrow aspirate is also obtained to evaluate MYD88 and CXCR4 mutational status

Additional diagnostics3:

- complete blood counts

- comprehensive metabolic panel

- immunoglobulins

- β-2 microglobulin

- cryoglobulins

- cold agglutinins

- baseline computed tomography scans

Risk assessment1

The International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) can be used if a patient with WM is symptomatic and treatment naïve. Risk factors include:

- age >65 years;

- hemoglobin ≤11.5 g/dL;

- platelet count ≤110 /L;

- serum beta-2 microglobulin >3 mg/L; and

- serum monoclonal protein >70 g/L.

Patients with 0–1 risk factors (excluding older age) are associated with low-risk disease and a median survival of 10 years. Two risk factors or older age alone are associated with intermediate-risk disease and a median survival of ≥8 years. Three or more risk factors are associated with high-risk disease and a median survival of 3.5 years.

Guidance on diagnosis may vary between countries. Please read the section on key guidelines for further information.

Management

Not all patients with WM require treatment at the time of diagnosis. The criteria for treatment initiation include4:

- the development of symptomatic anemia with a hemoglobin ≤10 g/dL that is secondary to WM;

- platelets <100,000 mm3;

- symptomatic hyperviscosity;

- moderate to severe neuropathy;

- symptomatic extramedullary disease; or

- other symptomatic complications of the disease such as cold agglutinin, cryoglobulinemia, or amyloidosis.

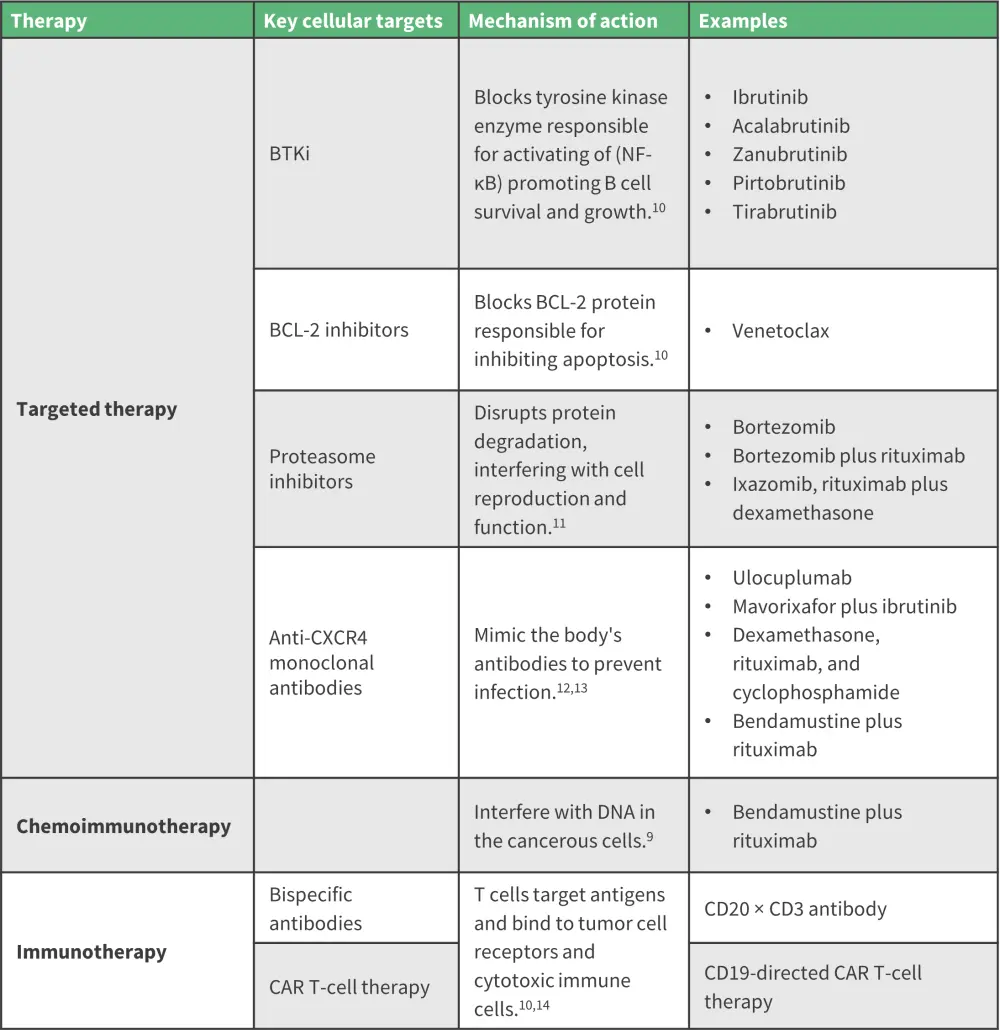

Treatment options have progressed in WM since advancements in high-technology sequencing have improved the understanding of the molecular landscape of WM.8 Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors have paved the way for the successful treatment of patients with newly diagnosed and relapsed/refractory WM.9 More emerging treatments are on the horizon, including chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy, novel B-cell lymphoma 2 inhibitors, proteasome inhibitors, and monoclonal/bispecific antibodies (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Summary of major types of therapy and cellular targets*

BCL-2, B-cell lymphoma 2; BTKi, Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CXCR4, chemokine receptor type 4; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells.

*Data from Moreno, et al.9; Amaador, et al.10; IMWF.11,12; Cancer Research UK13; Palomba, et al.14

Figure 5. Cancer treatment options*

*Created with BioRender.com

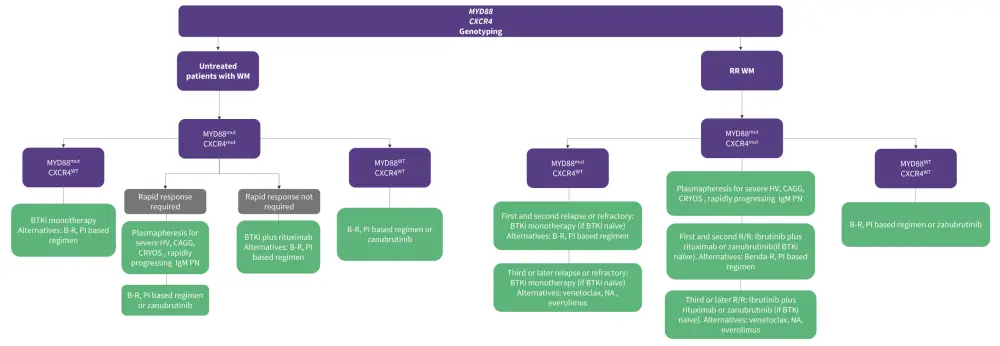

Since treatment options have progressed in the last decade, genomic-based algorithms have had a positive and widespread impact on treatment outcomes. The presence of MYD88/CXCR4 mutations can guide treatment options for patients. Treatment recommendations are also dependent on the stage (newly diagnosed or relapsed/refractory) of WM (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Treatment options for patients with de novo WM and R/R WM based on genotyping*

B-R, bendamustine and rituximab; BTKi, Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor; CAGG, cold agglutinin; CRYOS, cryoglobulinemia; HV, hyperviscosity; mut, mutated; NA, nucleoside analog; PI, proteasome inhibitor; R/R, relapsed/refractory; WM, Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia; wt, wild-type.

*Data adapted from Treon, et al.15

Guidance on diagnosis may vary between countries. Please read the below section on key guidelines for further information.

Key Guidelines and organizations

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content