All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the Lymphoma Coalition.

The lym Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the lym Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The lym and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Lymphoma & CLL Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by AbbVie, BeOne Medicines, Johnson & Johnson, Miltenyi Biomedicine, Nurix Therapeutics, Roche, Sobi, and Thermo Fisher Scientific and supported through educational grants from Bristol Myers Squibb, Lilly, and Pfizer. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View lymphoma & CLL content recommended for you

Educational theme │ Novel therapies for the treatment of first relapse and primary refractory disease in patients with classical Hodgkin Lymphoma

Do you know... PET-adapted approaches are utilized to determine patient responses to therapy and make subsequent treatment decisions. Patients with cHL who experience R/R disease following first-line therapy often undergo salvage therapy. What is the standard next step in managing patients who achieve a complete metabolic response to salvage therapy?

Although classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) can be cured with first-line therapy, approximately 10–30% of patients develop relapsed or refractory (R/R) disease.1 Of these patients, 50–60% show long-term progression-free survival (PFS) after standard salvage chemotherapy followed by high-dose chemotherapy (HDCT) and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (auto-HSCT). The treatment landscape for patients who experience disease relapse after auto-HSCT, or those who are considered ineligible for auto-HSCT, has evolved in the past decade, addressing the once limited treatment options and poor survival rates in this population. Novel therapies, including CD30-directed antibody-drug conjugate brentuximab vedotin (BV) and immune checkpoint inhibitors, have greatly improved complete metabolic response (CMR) rates prior to auto-HSCT, especially when combined with chemotherapy.

While achieving CMR prior to auto-HSCT is prognostic of PFS when using a risk and positron emission tomography (PET) adapted approach, the burden of late toxicities related to HDCT is considerable and hence equally important to consider in the treatment of R/R cHL. Evidence from early phase trials show promising results for these novel drugs, either used as monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy. However, evidence-based recommendations for optimal treatment sequencing for patients with R/R cHL is challenging in the absence of phase III randomized controlled trials.

As part of the educational theme series on the management of cHL, the Lymphoma Hub recently published an article on the first-line management of cHL. Here we present the second article in the series, providing an overview of studies that have incorporated novel therapies and response-adapted treatment approaches in patients with R/R cHL.1

First relapse or primary refractory disease after first-line therapy

Using computed tomography-based methods, conventional salvage chemotherapy prior to auto-HSCT has been shown to achieve complete response rates of 20–25% and overall response rates of 60–70%.

Recent studies, based on PET or gallium imaging, reported the following CMR rates:

- ICE (ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide) / ESHAP (etoposide, methylprednisolone, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin): 50%–60%

- BeGEV (bendamustine, gemcitabine, and vinorelbine): 73% (NCT01884441)

- Sequential ICE–GVD (gemcitabine, vinorelbine, and liposomal doxorubicin): 78% (NCT00255723)

Patient outcomes were not significantly different across these studies, with 5-year PFS ranging from 50–60% and overall survival from 70–80%. The author notes a lack of randomized controlled trials comparing different salvage chemotherapy regimens or using PET-adapted approach.

BV and checkpoint inhibitors

First salvage therapy using BV in combination with chemotherapy was investigated in several studies and has shown encouraging CMR rates (Table 1). PFS was similar for patients who proceeded to auto-HSCT directly after having a CMR with BV, BV-nivolumab, or ICE alone and for those that needed additional salvage chemotherapy.

Table 1. Studies evaluating first salvage regimens with BV or CPIs*

|

Auto-HSCT, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; BV, brentuximab vedotin; CMR; complete metabolic response; CPI, checkpoint inhibitor; DHAP, dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin; ESHAP, etoposide, methylprednisolone, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin; GVD, gemcitabine, vinorelbine, and liposomal doxorubicin; HDCT, high-dose chemotherapy; ICE, ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide; IGEV, ifosfamide, gemcitabine, vinorelbine, and prednisolone; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression free survival. |

||||||

|

Study |

N |

Intervention |

Refractory, |

CMR pre-auto- |

2-year |

2-year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Moskowitz 2017 |

65 |

BV + sequential |

52 |

83 |

82 |

97 |

|

Herrera 2018 |

57 |

BV + sequential |

61 |

65 |

67 |

93 |

|

Cole 2018 |

45 |

BV + gemcitabine |

64 |

67 |

— |

95† |

|

LaCasce 2018 |

55 |

BV + |

51 |

74 |

63 |

94 |

|

66 |

BV + ESHAP |

61 |

70 |

71 |

90 |

|

|

Broccoli 2019 |

40 |

BV + |

50 |

79 |

68 |

97 |

|

Abuelgasim |

28 |

BV + IGEV |

43 |

70 |

74 |

87 |

|

67 |

BV + DHAP |

45 |

82 |

78 |

96 |

|

|

Advani 2021 |

91 |

BV + nivolumab |

42 |

67 |

78 |

93 |

|

39 |

Pembrolizumab + |

41 |

95 |

100† |

100† |

|

HDCT and auto-HSCT

Short-term toxicities such as cytopenias and mucositis and long-term toxicities such as infertility and secondary malignancies have been attributed to HDCT and auto-HSCT; however, past studies have highlighted the superiority of HDCT and auto-HSCT over reduced dose BEAM (carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, and melphalan) without auto-HSCT in patients with R/R cHL. In a recent study (NCT03618550), pembrolizumab plus GVD chemotherapy demonstrated a pre-transplant CMR rate of 95%. The second phase of this study has been initiated; patients with CMR after two cycles will receive two additional cycles of pembrolizumab-GVD followed by pembrolizumab consolidation, which will replace HDCT/auto-HSCT. If successful, this approach could spare patients harsh side effects.

Primary refractory disease

Patients with refractory cHL showed lower CMR rates compared to those who have relapsed (73% vs 86% after DHAP; 64% vs 84% BV-bendamustine; 53% vs 77% BV-nivolumab, respectively) however, post auto-HSCT PFS was similar in patients with primary refractory and relapse. Data from a retrospective analysis highlight the favorable outcomes achieved with CPI-containing regimens, with 59% of patients achieving CMR and 18-month PFS rate of 81%, suggesting CPI may improve chemosensitivity.

Late relapse

Patients with early-stage favorable disease were more susceptible to late relapse compared to those with unfavorable or advanced stage disease in a large retrospective study. Auto-HSCT was associated with favorable PFS and overall survival in nearly half of these patients compared to other salvage therapies. Depending on patient’s initial treatment and underlying comorbidities, non-HSCT approaches such as combination chemotherapy or radiation alone could be considered.

Post auto-HSCT maintenance and the role of radiotherapy

In the phase III AETHERA study, maintenance therapy with BV demonstrated a 5-year PFS of 59% compared with 41% for placebo. This data suggests that BV maintenance in patients with at least two risk factors could be either restricted to this subset or delayed until disease progression. CPI maintenance could be used in patients who relapse post BV + chemotherapy. In patients with residual lesions, extranodal or bulky disease, radiotherapy can be used pre- and post-auto-HSCT. Radiotherapy may also be an option for patients with limited-stage disease at relapse, previous studies have reported a decreased risk of local recurrence in patients receiving radiotherapy.

BV and CPI in patients who relapse following auto-HSCT or ineligible for auto-HSCT

The most recent studies evaluating BV and CPI in patients with R/R cHL who have poor prognosis after at least one line of salvage treatment are summarized in Table 2. The findings suggest comparable response rates between patients who received earlier treatment with BV or CPI and those who did not.

Table 2. Studies evaluating BV or CPI after ≥1 line of salvage therapy*

|

BV, brentuximab vedotin; CMR; complete metabolic response; CPI, checkpoint inhibitor; ORR, overall response rate; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression free survival. |

||||||

|

Study |

N |

Intervention |

CMR, % |

ORR, % |

PFS, % |

OS, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

102 |

BV |

34 |

75 |

5 years–22 |

5 years–41 |

|

|

O’Connor 2018 (NCT01657331) |

65 |

BV + bendamustine |

32 |

71 |

2 years–50† |

2-years–65† |

|

243 |

Nivolumab |

16 |

69 |

1 year–50† |

1 year–92 |

|

|

210 |

Pembrolizumab |

28 |

72 |

2 years–31 |

2 years–91 |

|

|

Shi 2019 (NCT03114683) |

92 |

Sintilimab |

34 |

80 |

6 month–78 |

6 month–100 |

|

75 |

Camrelizumab |

28 |

76 |

9 month–77 |

9 month–96† |

|

|

Armand 2020 (NCT01953692) |

31 |

Pembrolizumab |

19 |

58 |

2 years–30 |

2 years–87 |

|

70 |

Tislelizumab |

64 |

87 |

9 month–75 |

9 month–99 |

|

|

64 |

Ipilimumab + BV vs nivolumab + BV vs ipilimumab + nivolumab + BV |

60/65/84 |

80/94/95 |

1 year–59/77/87 |

1 year–90/80/95† |

|

|

304 |

Pembrolizumab (n = 151) vs BV (n = 152) |

25 vs 24 |

66 vs 54 |

2 years–35 vs 25 |

— |

|

|

Liu 2021 (NCT02961101; NCT03250962) |

61 |

Camrelizumab monotherapy vs camrelizumab + decitabine |

79 vs 32 for camrelizumab + decitabine vs camrelizumab |

95 vs 89 |

2 years–67 vs 42 |

2 years–100 |

PET-adapted treatment for R/R cHL

Of the studies utilizing PET-adapted treatment approaches for cHL, PFS is comparable between patients proceeding to autologous stem cell transplant after achieving a CMR with BV, BV-nivolumab, or ICE and those patients requiring further salvage chemotherapy to obtain a CMR. These findings emphasize that achieving CMR prior to auto-HSCT is quintessential to the success of salvage therapy in patients with disease that does not respond to frontline treatment.

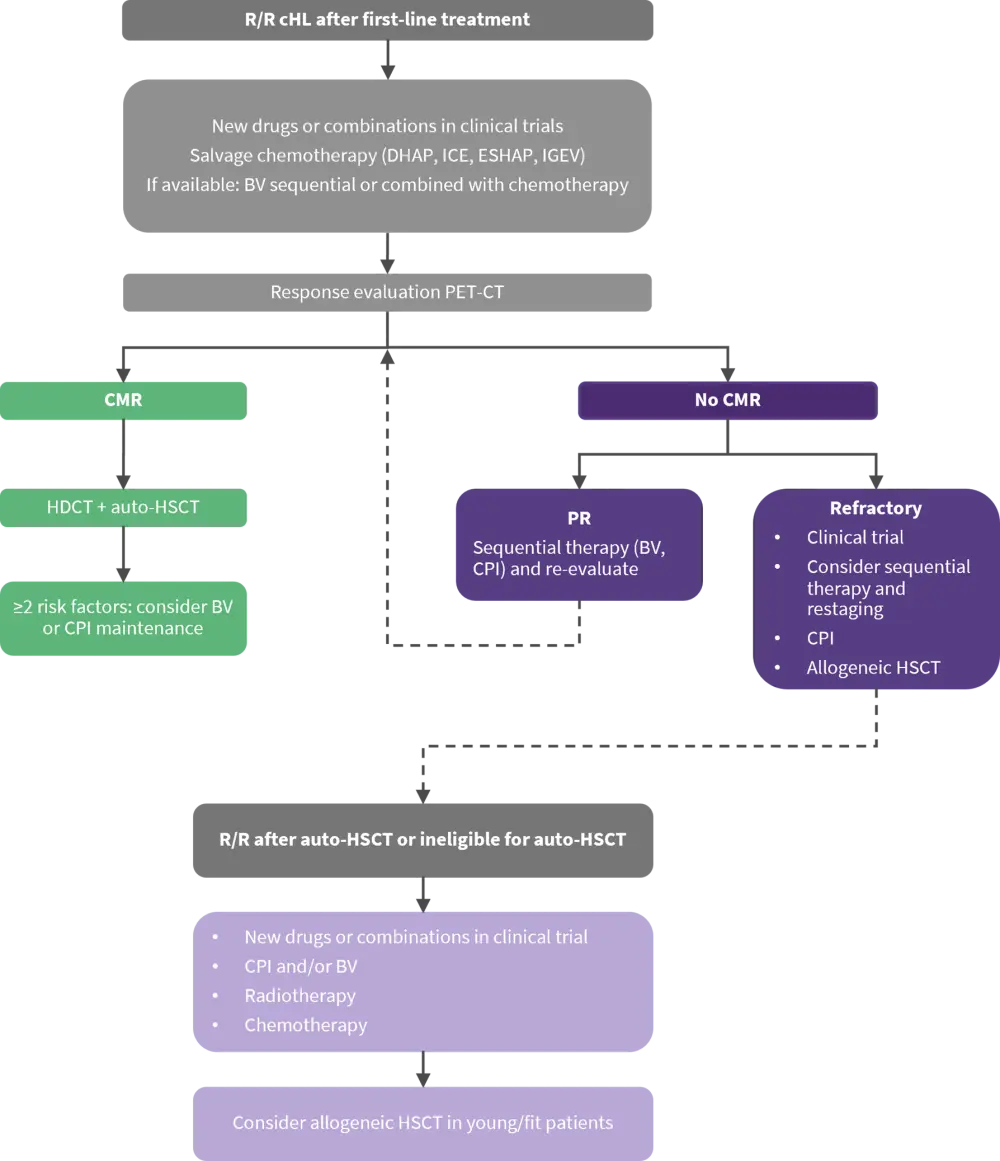

BV and CPI are not offered as first salvage treatment in numerous countries, salvage chemotherapy is still the standard approach. Figure 1 proposes a PET-adapted treatment approach in patients with R/R cHL.

Figure 1. Proposed treatment schema for R/R cHL*

Auto-HSCT, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; BV, brentuximab vedotin; cHL, classical Hodgkin lymphoma; CMR; complete metabolic response; CPI, checkpoint inhibitor; DHAP, dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin; ESHAP, etoposide, methylprednisolone, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin; HDCT, high-dose chemotherapy; ICE, ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide; IGEV, ifosfamide, gemcitabine, vinorelbine, and prednisolone; PR, partial response; PET-CT, positron emission tomography-computed tomography; R/R, relapsed/refractory.

*Adapted from Driessen, et al.1

Conclusion

This review demonstrated that achieving CMR before HDCT/auto-HSCT is significantly correlated with favorable outcomes after auto-HSCT. A sequential treatment approach reduced toxicity in a subset of fast-responding patients. BV and CPI could be offered to patients who are ineligible for auto-HSCT or relapse after auto-HSCT, but further studies are required to balance the efficacy and toxicity of these novel agents. Prospective studies are warranted to investigate which group of patients can be treated without HDCT/auto-HSCT using risk-stratified and PET-adapted approach. Research is also needed to investigate the role of post auto-HSCT maintenance in high‑risk patients with CPI and/or BV over reserving these treatments for a subsequent relapse. Studies investigating radiotherapy in patients who have primary refractory disease prior to auto-HSCT are needed, including research into the synergistic effects of radiation with immunotherapy.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content