All content on this site is intended for healthcare professionals only. By acknowledging this message and accessing the information on this website you are confirming that you are a Healthcare Professional. If you are a patient or carer, please visit the Lymphoma Coalition.

The lym Hub website uses a third-party service provided by Google that dynamically translates web content. Translations are machine generated, so may not be an exact or complete translation, and the lym Hub cannot guarantee the accuracy of translated content. The lym and its employees will not be liable for any direct, indirect, or consequential damages (even if foreseeable) resulting from use of the Google Translate feature. For further support with Google Translate, visit Google Translate Help.

The Lymphoma & CLL Hub is an independent medical education platform, sponsored by AbbVie, BeOne Medicines, Johnson & Johnson, Miltenyi Biomedicine, Nurix Therapeutics, Roche, Sobi and Thermo Fisher Scientific and supported through educational grants from Bristol Myers Squibb, Lilly and Pfizer. Funders are allowed no direct influence on our content. The levels of sponsorship listed are reflective of the amount of funding given. View funders.

Now you can support HCPs in making informed decisions for their patients

Your contribution helps us continuously deliver expertly curated content to HCPs worldwide. You will also have the opportunity to make a content suggestion for consideration and receive updates on the impact contributions are making to our content.

Find out more

Create an account and access these new features:

Bookmark content to read later

Select your specific areas of interest

View lymphoma & CLL content recommended for you

Options for the treatment of second-line DLBCL

Do you know... What is the preferred treatment option for second-line DLBCL if relapse occurs >12 months after diagnosis?

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, accounting for 25–30% of cases, characterized by its aggressive and rapidly growing nature.1 First-line therapies for DLBCL include the rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) regimen, which yields prolonged remissions in >60% of patients with advanced-stage disease.2 However, despite these advancements in the first-line a substantial proportion of patients experience primary refractory disease or relapse after initial treatment, with 30–40% relapsing and a significant portion refractory to further treatments.3 For these patients, second-line therapy becomes a critical component of management.

The aim of second-line therapy is to achieve disease remission or significant disease control to enable subsequent treatment strategies, such as high-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT). The choice of second-line treatment is influenced by various factors, including the patient's prior treatment response, overall health status, and specific disease characteristics.4

Challenges in second-line therapy

Developing treatment strategies for relapsed/refractory (R/R) DLBCL poses a multitude of challenges, including:

- Treatment resistance: Patients with primary refractory disease or early relapse, within 12 months, tend to have poor outcomes with conventional second-line therapies as the cells often become resistant to chemotherapy and immunotherapy.5

- Toxicity and patient fitness: Second-line treatments, such as intensive chemotherapy regimens or ASCT, are associated with considerable toxicity. Older adults and those with substantial comorbidities, may be ineligible for these therapies.6

- Access to novel therapies: Novel therapies such as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies, bispecific antibodies, and targeted agents have shown promising efficacy but are not available to all patients, in part due to logistical, financial, or regulatory barriers.6

- As an example, the complexity of administering CAR T-cell therapy, including the need for specialized centers and careful patient monitoring, limits its accessibility for many patients.

Treatment options

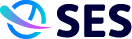

In recent years, the number of options available for patients with R/R DLBCL has considerably increased. Selection criteria for second-line DLBCL treatments are typically divided by time of relapse, as well as eligibility for ASCT and CAR T-cell therapy.7

Figure 1. Proposed treatment algorithm for second-line R/R DLBCL*

ASCT, autologous stem cell transplant; BR, bendamustine + rituximab; CAR-T, chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; HDT, high-dose therapy; R-CHOP, rituximab + cyclophosphamide + doxorubicin + vincristine + prednisone; R/R, relapsed/refractory.

*Data from Fabbri, et al.4

Transplant-eligible late relapsed DLBCL7

Patients who experience late relapses, occurring after >12 months, typically experience improved outcomes and have a more favorable risk profile than those who relapse earlier.

Among these patients, where transplant is available, ASCT has been the preferred option. For a subset of patients with R/R DLBCL, particularly those who achieve remission or respond well to salvage chemotherapy, ASCT offers a potentially curative option providing long-term remission in many cases, solidifying its role as standard of care (SoC) therapy in younger and fit patients with R/R DLBCL. ASCT has also proven most effective in patients who responded well to chemotherapy before their transplant. These patients are more likely to achieve durable remission after high-dose chemotherapy and transplant. However, ASCT is limited to patients who are fit enough to tolerate the intensive therapy and have chemotherapy-sensitive disease.

Salvage chemotherapies are typically delivered prior to ASCT to enhance outcomes. The most common regimens are rituximab + ifosfamide + carboplatin + etoposide (R-ICE) and rituximab + dexamethasone + high-dose cytarabine + cisplatin (R-DHAP).

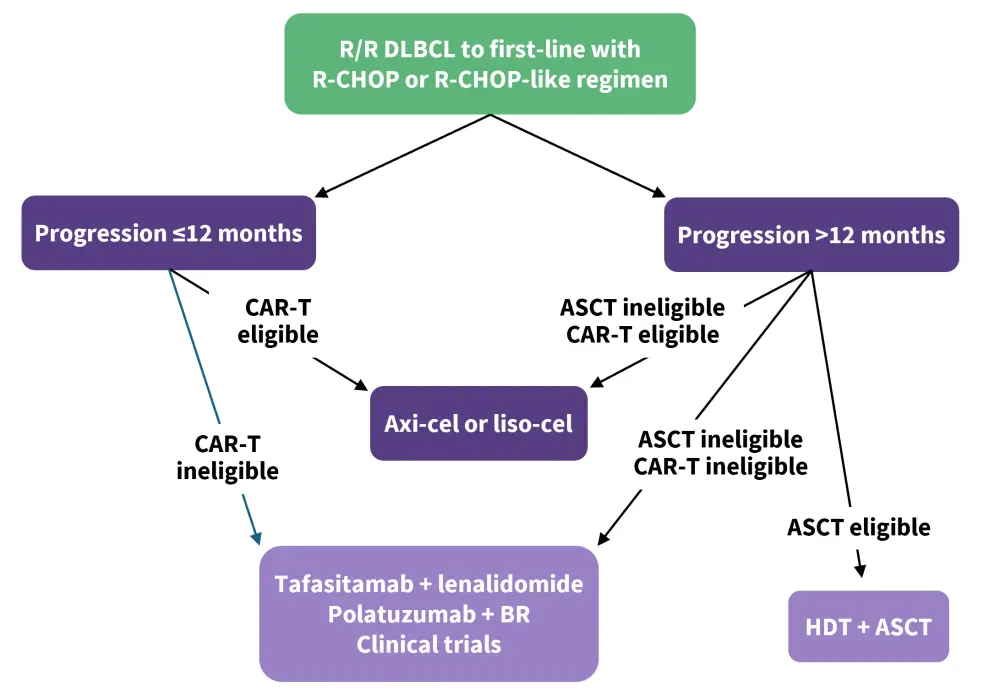

There are a number of novel therapeutic combinations being explored to enhance outcomes to salvage therapy. Promising results have been seen with regimens incorporating novel agents like polatuzumab vedotin with R-ICE (Figure 2), as well as other combinations of existing chemotherapies. These combinations have shown encouraging response rates, including in high-risk patients with primary refractory disease. Ongoing research is evaluating various other novel drug combinations in this setting, with the aim to optimize outcomes for transplant-eligible patients, especially those with high-risk DLBCL subgroups.

Figure 2. Response rates to polatuzumab vedotin in combination with R-ICE from the phase II Pola-R-ICE study*

CR, complete response; ORR, overall response rate; PR, partial response; R-ICE, rituximab + ifosfamide + carboplatin + etoposide.

*Data from Herrera, et al.7

Transplant-ineligible/CAR T-cell therapy-eligible DLBCL

Regardless of when relapse occurrs, where patients are ineligible for ASCT, they are evaluated for eligibility to CAR T-cell therapies as an alternative. Axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel) and lisocabtagene maraleucel (liso-cel) are currently the only two CD19-directed CAR T-cell therapies that are approved in the second-line for R/R DLBCL; based on data from the ZUMA-7 and TRANSFORM trials.8,9

Axi-cel10

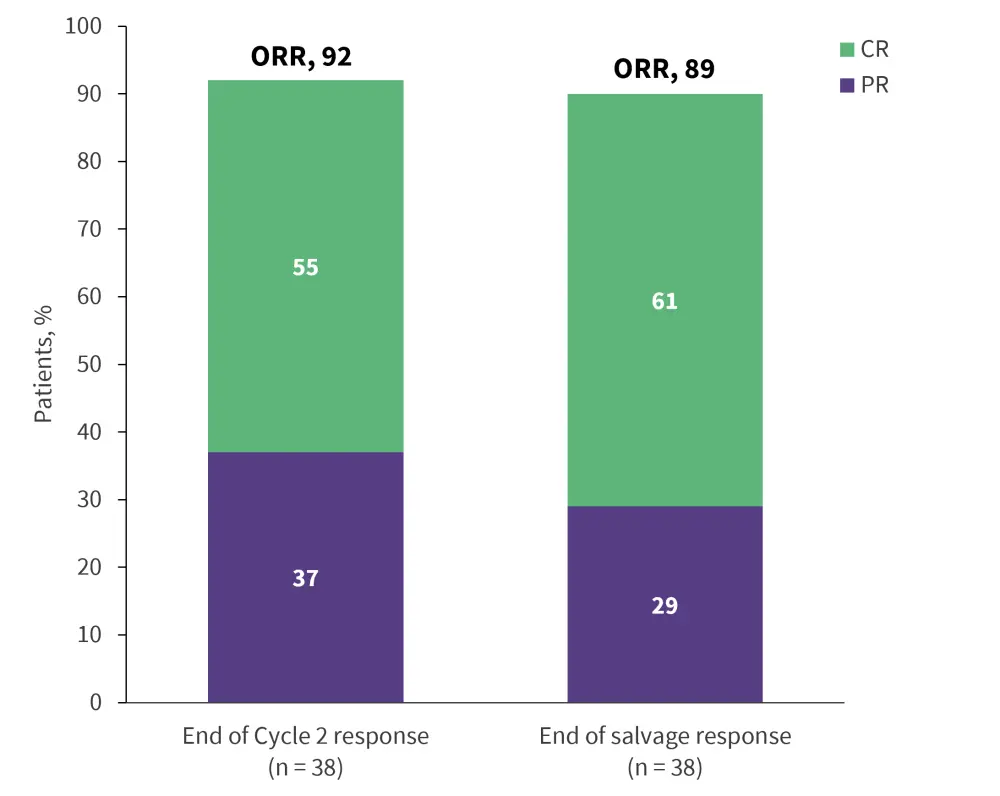

ZUMA-7 (NCT03391466) is a phase III clinical trial that evaluated the efficacy and safety of axi-cel in patients with R/R DLBCL. The trial compared axi-cel to standard second-line treatment options, typically salvage chemotherapy and ASCT.

Treatment with axi-cel resulted in a significantly higher response rate than SoC therapies, with 65% reaching a complete response, compared with 32% following SoC (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Overall response rate of axi-cel vs SoC from ZUMA-7*

Axi-cel, axicabtagene ciloleucel; CR, complete response; NE, not evaluable; ORR, overall response rate; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

*Data from Locke, et al.10

Additional key efficacy data:

- Median event-free survival (EFS) was significantly improved following treatment with axi-cel at 8.3 months compared with 2.0 months with SoC.

- Median OS was not reached with axi-cel compared with 35.1 months with SoC.

- Median progression-free survival (PFS) was also significantly improved at 14.7 months compared with 3.7 months with SoC.

The incidence of any adverse event (AE) was largely comparable between the two treatment arms; however, the rates of hematologic toxicities were significantly higher with axi-cel. There were also high rates of cytokine release syndrome (CRS) observed with axi-cel, but a substantial portion of these were low grade (Table 1).

Table 1. Adverse events associated with axi-cel treatment*

|

AE, adverse event; axi-cel, axicabtagene ciloleucel; CRS, cytokine release syndrome; SoC, standard of care. |

||||

|

AEs, % |

Axi-cel |

SoC |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Any grade |

Grade ≥3 |

Any grade |

Grade ≥3 |

|

|

Any AE |

100 |

91 |

100 |

83 |

|

Pyrexia |

93 |

9 |

26 |

1 |

|

Neutropenia |

71 |

69 |

42 |

41 |

|

Hypotension |

44 |

11 |

15 |

3 |

|

Fatigue |

42 |

6 |

52 |

2 |

|

Anemia |

42 |

30 |

54 |

39 |

|

Diarrhea |

42 |

2 |

39 |

4 |

|

Headache |

41 |

3 |

26 |

1 |

|

Nausea |

41 |

2 |

69 |

5 |

|

Sinus tachycardia |

34 |

2 |

10 |

1 |

|

Leukopenia |

32 |

29 |

26 |

22 |

|

Thrombocytopenia |

29 |

15 |

60 |

57 |

|

Hypokalemia |

26 |

6 |

29 |

7 |

|

Hypophosphatemia |

26 |

18 |

17 |

12 |

|

CRS |

92 |

6 |

— |

— |

|

Neurologic event |

60 |

21 |

20 |

1 |

Liso-cel11

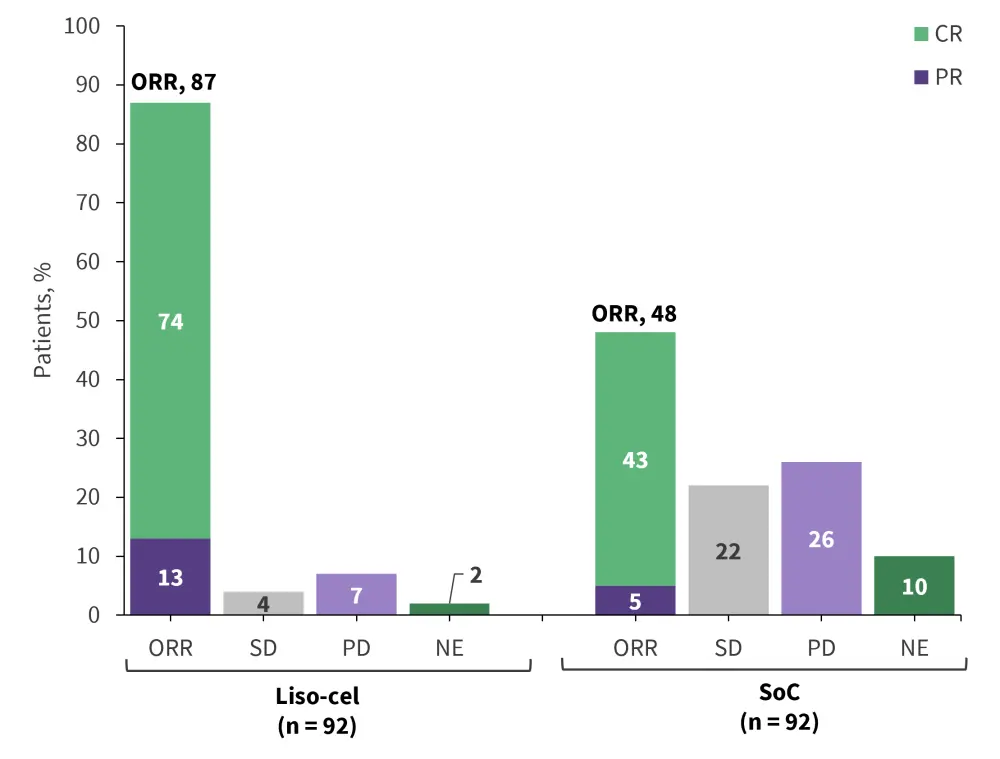

TRANSFORM (NCT03575351) is a phase II clinical trial that evaluated the efficacy and safety of liso-cel as a second-line treatment for patients with R/R LBCL, including DLBCL. The trial compared liso-cel with the SoC of salvage chemotherapy followed by ASCT for eligible patients.

Following treatment with liso-cel, neither median EFS, PFS, nor OS were reached in the follow-up period compared with 2.4 months, 6.2 months, and 29.9 months with SoC, respectively. The overall response rate was significantly higher in patients receiving liso-cel compared with the SoC therapies (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Overall response rate of liso-cel vs SoC from TRANSFORM*

CR, complete response; liso-cel, lisocabtagene maraleucel; ORR, overall response rate; NE, not evaluable; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; SoC, standard of care.

*Data from Abramson, et al.11

The incidence of infections and CRS was of particular interest following treatment with liso-cel. However, the incidence of higher grade (Grade ≥3) CRS was low, occurring in 1% of patients. The rate of severe infections was numerically higher with SoC, although hypogammaglobulinemia was significantly more common with liso-cel (Table 2).

Table 2. Adverse events of special interest with liso-cel*

|

AE, adverse event; CRS, cytokine release syndrome; liso-cel, lisocabtagene maraleucel; SoC, standard of care. |

||

|

AE, % |

Liso-cel |

SoC |

|---|---|---|

|

CRS |

|

|

|

Any grade |

49 |

— |

|

Grade 1 |

37 |

— |

|

Grade 2 |

11 |

— |

|

Grade 3 |

1 |

— |

|

Neurological events |

|

|

|

Any grade |

11 |

— |

|

Grade 1 |

4 |

— |

|

Grade 2 |

2 |

— |

|

Grade 3 |

4 |

— |

|

Severe infections, |

15 |

21 |

|

Hypogammaglobulinemia |

11 |

3 |

Selecting CAR T-cell therapies

In a meta-analysis of outcomes following treatment with axi-cel and liso-cel by Gagelmann et al.12, there were significantly improved response rates and PFS observed in patients who received axi-cel. Overall survival (OS) also appeared to be associated with odds in favor of axi-cel, as well as non-relapse mortality. In terms of CAR T-cell therapy-specific toxicities, axi-cel showed higher odds for occurrence of CRS of any grade; however, there were no significant differences between the two CAR T-cell therapies for severe CRS at Grade ≥3. Axi-cel was consistently associated with the occurrence of immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) of any grade and for severe AEs.12

Transplant- and CAR T-cell therapy-ineligible DLBCL

For patients who are ineligible for both ASCT and CAR T-cell therapy, effective management of disease is more challenging. There are a number of treatment options that can be considered based on disease and patient characteristics as well as patient preferences and safety profiles. These options typically focus on managing the disease with novel therapies and combinations to improve outcomes for difficult to treat patients.

The standard therapies for ineligible patients has historically involved multi-agent chemoimmunotherapy regimens, including rituximab + gemcitabine + oxaliplatin (R-GemOx) and bendamustine + rituximab (BR).4 Where newer options are not available, these two combinations present an option with tolerable safety profiles but less than optimal response data.4 Currently, tafastimab + lenalidomide and polatuzumab vedotin + bendamustine + rituximab are the two preferred therapies for transplant and CAR T-cell therapy-ineligible R/R DLBCL in the second-line.13

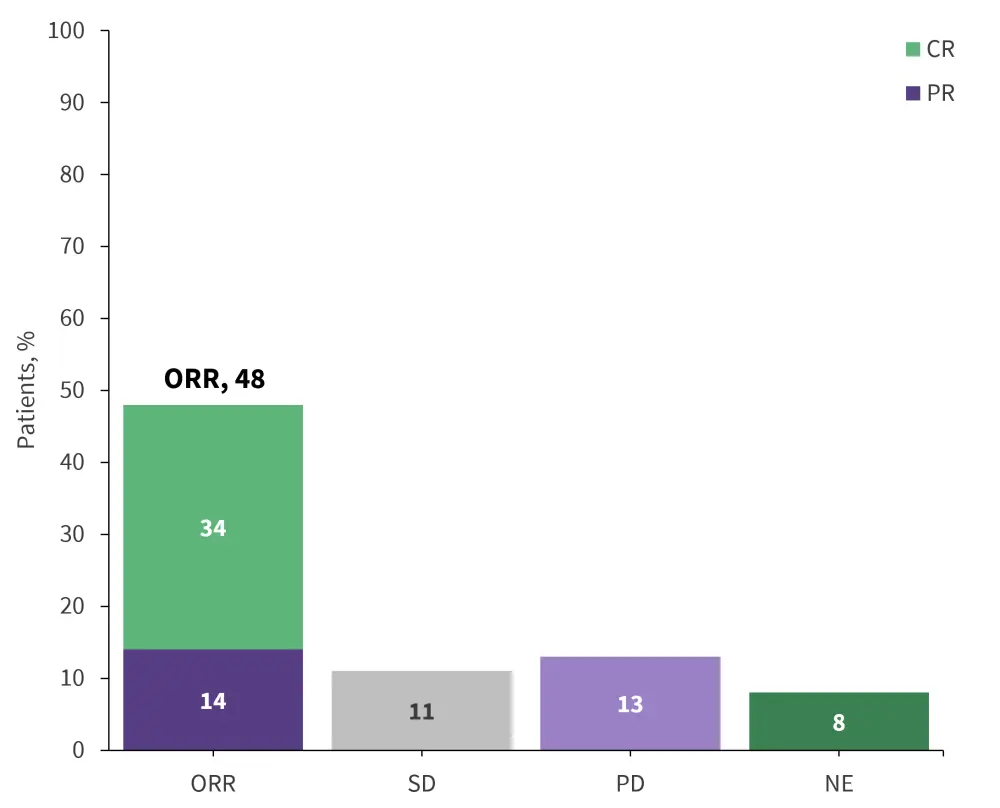

Tafasitamab14

Tafasitamab is a monoclonal antibody that binds to CD19, a protein on the surface of lymphoma cells, resulting in the lysis of B cells. Tafasitamab in combination with lenalidomide was investigated as part of the phase II L-MIND study.

The combination of tafasitamab and lenalidomide resulted in an overall response rate of 48%, with 34% being a complete response (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Response data for tafasitamab in combination with lenalidomide*

CR, complete response; NE, not evaluable; ORR, overall response rate; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

*Data from Salles, et al.14

- Median duration of response (DoR) was 21.7 months; however, among the patients who experienced a CR, the median DoR was not reached.

- Median PFS was 12.1 months, with a 12-month PFS rate of 50%.

- At a median follow-up of 19.6 months, median OS was not reached, with a 12-months OS rate of 74% and 18-month PFS rate of 64%.

Serious AEs were reported in 51% of patients, with the most frequently observed events being pneumonia and febrile neutropenia at 6%, followed by pulmonary embolism in 4%, and bronchitis, atrial fibrillation, and congestive heart failure in 2%. Treatment-related serious AEs occurred in 19% of patients, with 10% being infections, such as bronchitis, pneumonia, sepsis, and respiratory infections. Febrile neutropenia was observed in 5% of patients. Other treatment-related serious events included pulmonary embolism, along with isolated cases of agranulocytosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, fatigue, pyrexia, atrial fibrillation, and tumor flare.

Overall, this combination was well tolerated and led to a high proportion of patients with R/R DLBCL ineligible for ASCT achieving a complete response; consolidating the use of this combination in clinical practice and leading to its accelerated approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Polatuzumab vedotin14

Polatuzumab vedotin is an antibody–drug conjugate (ADC) that binds to the CD79b protein on the surface of B cells and delivers the cytotoxic agent monomethyl auristatin E into the cytosol of the cell, resulting in cell death.

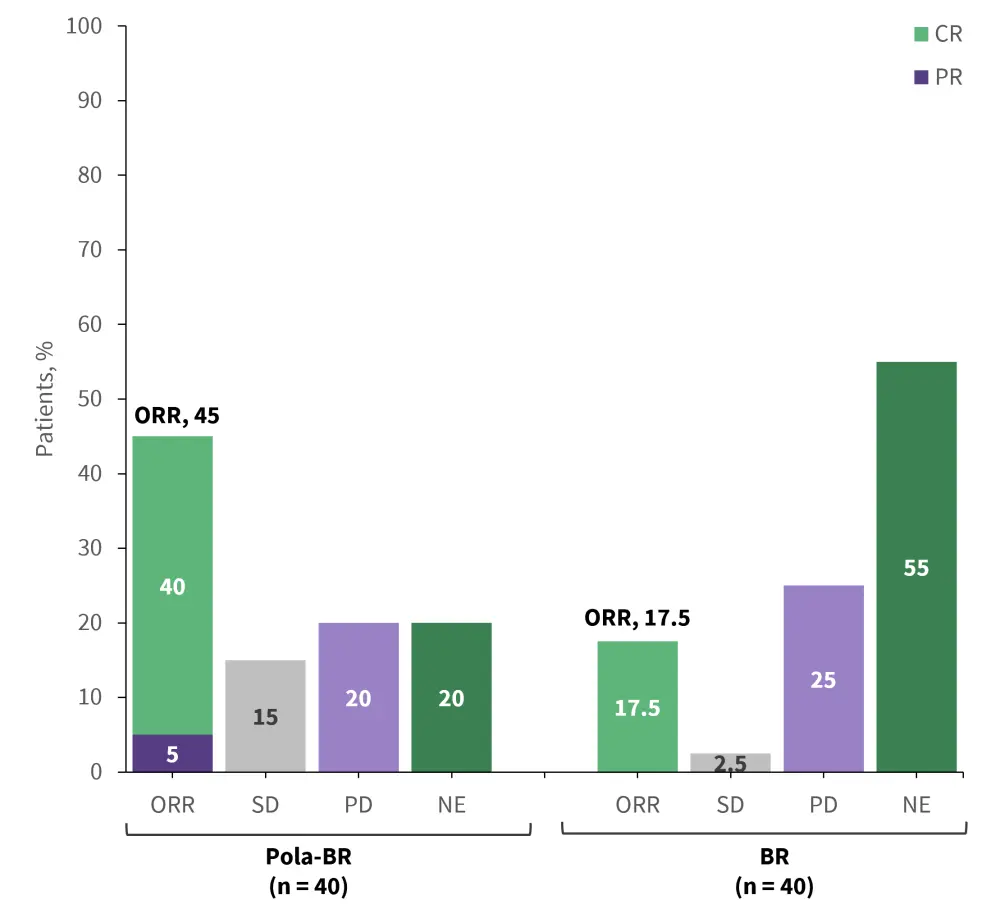

As part of a randomized phase I/II trial (NCT02257567), polatuzumab vedotin combined with bendamustine + rituximab (pola-BR) was evaluated against bendamustine + rituximab (BR) in patients with R/R DLBCL who were ineligible for ASCT. The primary endpoint of the study was the complete response (CR) rate at the end of treatment, as assessed by an independent review committee. At a median follow-up of 22.3 months, a significantly higher median PFS, OS, and DOR were observed with pola-BR compared with BR. The combination of pola-BR also resulted in a significantly higher CR rate compared with BR alone (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Response rate associated with Pola-BR and BR in R/R DLBCL*

BR, bendamustine + rituximab; CR, complete response; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; NE, not evaluable; ORR, overall response rate; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; Pola-BR, polatuzumab vedotin + bendamustine + rituximab; R/R, relapsed/refactory; SD, stable disease.

*Data from Sehn, et al.15

Following treatment with pola-BR and BR:

- Median OS was 11.8 months and 4.7 months, respectively

- Median PFS 9.5 months and 3.7 months, respectively

- Median DoR 10.9 months and 7.7 months, respectively

Hematologic toxicities were typically higher in patients treated with pola-BR, with the most commonly occurring being anemia and neutropenia, recorded in >50% of patients treated with pola-BR. There were also higher rates of peripheral neuropathy recorded with pola-BR; however, there were no serious cases Grade ≥3 (Table 3).

Table 3. Adverse events following treatment with pola-BR and BR*

|

AE, adverse events; BR, bendamustine + rituximab; Pola-BR, polatuzumab vedotin + bendamustine + rituximab. |

||||

|

AE, % |

Pola-BR |

BR |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Any grade |

Grade 3/4 |

Any grade |

Grade 3/4 |

|

|

Anemia |

53.8 |

28.2 |

25.6 |

17.9 |

|

Neutropenia |

53.8 |

46.2 |

38.5 |

33.3 |

|

Thrombocytopenia |

48.7 |

41.0 |

28.2 |

23.1 |

|

Lymphopenia |

12.8 |

12.8 |

0 |

0 |

|

Febrile neutropenia |

10.3 |

10.3 |

12.8 |

12.8 |

|

Diarrhea |

38.5 |

2.6 |

28.2 |

2.6 |

|

Nausea |

30.8 |

0 |

41.0 |

0 |

|

Constipation |

17.9 |

0 |

20.5 |

2.6 |

|

Fatigue |

35.9 |

2.6 |

35.9 |

2.6 |

|

Pyrexia |

33.3 |

2.6 |

23.1 |

0 |

|

Decreased appetite |

25.6 |

2.6 |

20.5 |

0 |

|

Peripheral neuropathy |

43.6 |

0 |

7.7 |

0 |

Overall, for patients with transplant- and CAR T-cell therapy-ineligible R/R DLBCL, the combination of pola-BR led to a significantly higher CR rate and lowered the risk of death by 58% compared with BR alone.

Ongoing trials

Additional combination therapies with polatuzumab vedotin or tafasitamab are being investigated for the treatment of ASCT-ineligible and CAR T-cell therapy-ineligible R/R DLBCL (Table 4).

Table 4. Trials of combination therapies with polatuzumab vedotin or tafasitamab for R/R DLBCL*

|

R/R DLBCL, relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; R-GDP, rituximab + gemcitabine + dexamethasone + cisplatin; R-ICE, rituximab + ifosfamide + carboplatin + etoposide. |

||

|

Regimen |

Phase |

Trial |

|---|---|---|

|

Polatuzumab + R-GDP |

II |

|

|

Polatuzumab + mosunetuzumab |

III |

|

|

Polatuzumab + R-ICE |

III |

|

|

Polatuzumab + zanubrutinib + rituximab |

II |

|

|

Tafasitamab + golcadomide |

I/II |

|

|

Tafasitamab + maplirpacept + lenalidomide |

Ib/II |

|

|

Tafasitamab + mosunetuzumab + polatuzumab + lenalidomide |

II |

|

|

Tafasitamab + bendamustine |

II/III |

|

|

Tafasitamab + mosunetuzumab + polatuzumab + lenalidomide |

I |

|

|

Tafasitamab + lenalidomide + zanubrutinib |

II |

|

Future perspectives4

Several new agents are being investigated for R/R DLBCL, particularly in the second-line. Though not yet approved for this setting, ongoing trials aim to evaluate their efficacy, either as monotherapies or in combination.

- Loncastuximab tesirine is a CD19-directed antibody–drug conjugate that was previously approved by the FDA and European Medicines Agency (EMA) for use in patients with R/R DLBCL following ≥2 prior lines of therapy, based on data from the phase II LOTIS-2 (NCT03589469) trial. Loncastuximab tesirine is now being investigated in earlier lines including the second-line.

- Selinexor is an oral selective inhibitor of XPO1-mediated nuclear export, which acts to increase nuclear tumor suppressor proteins and suppress oncoprotein production, leading to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Selinexor is currently approved by the FDA after ≥2 lines of systemic therapy and is being investigated for use in the second-line.

- There are a number of bispecific antibody therapies currently under investigation, including mosunetuzumab, odronextamab, plamotamab, glofitamab, and epcoritamab. Data exist for glofitamab, epcoritamab, and odronextamab, establishing promising efficacy and manageable safety profiles in R/R DLBCL. The favorable efficacy and manageable toxicity profiles of these bispecific antibodies make them promising candidates for combination therapies in ongoing trials.

- In addition to these agents, several new targeted therapies are being explored for R/R DLBCL, including epigenetic modulators, new immunomodulators, MALT1 inhibitors, and IRAK4 inhibitors.

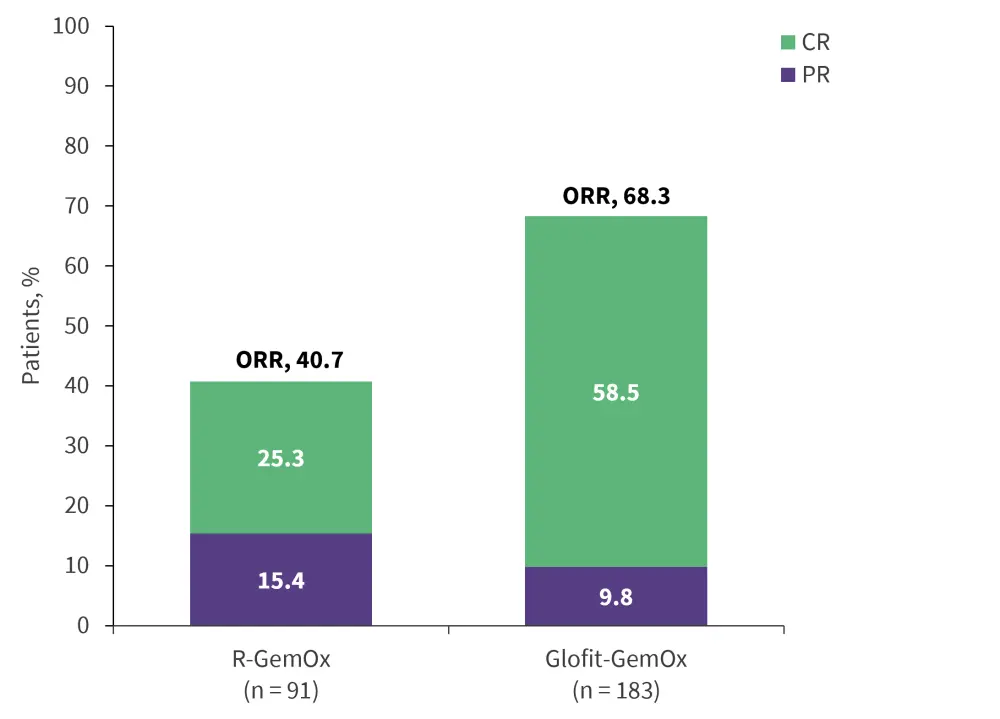

Glofitamab15

Glofitamab is a bispecific antibody therapy that acts by targeting CD20 on B cells and CD3 on T cells, resulting in immune activation and B cell death. Glofitamab is currently being evaluated as part of the phase III STARGLO(NCT04408638) study in combination with gemcitabine + oxaliplatin (Glofit-GemOx) for the treatment of R/R DLBCL.

On April 15, 2024, it was announced that STARGLO met its primary endpoint of OS.

- After a median follow-up of 20.7 months, the median OS was 25.5 months in the Glofit-GemOx group compared with 12.9 months in the R-GemOx group (hazard ratio [HR], 0.62; p = 0.006).

- Glofit-GemOx also showed improved PFS and a higher CR rate compared with R-GemOx. Median PFS was 13.8 months vs 3.6 months (HR, 0.40; p < 0.000001) and CR rates were 58.5% vs 25.3% (p < 0.0001), respectively (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Response data from STARGLO*

CR, complete response; Glofit-GemOx, glofitamab + gemcitabine + oxaliplatin; ORR, overall response rate; PR, partial response; R-GemOx, rituximab + gemcitabine + oxaliplatin.

*Data from Abramson.16

Glofitamab previously obtained accelerated approval from the FDA and conditional marketing authorization from the European Commission (EC) for the treatment of patients with R/R DLBCL after ≥2 prior lines of systemic therapy.

These data indicate that glofitamab when used in combination with gemcitabine and oxaliplatin has the potential to improve survival outcomes in earlier lines of treatment for patients with R/R DLBCL, who currently have limited treatment options.

Conclusion

For patients eligible for transplant, ASCT remains the preferred treatment option if relapse occurs >12 months after diagnosis. In contrast, anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy is now the favored approach for high-risk DLBCL, characterized by primary refractory disease or relapse within 12 months. Historically, treatment options were limited for patients ineligible for transplant or CAR T-cell therapy. However, recent approvals of therapies such as polatuzumab vedotin combined with bendamustine + rituximab, and tafasitamab with lenalidomide, have expanded the available options. Additionally, novel agents like loncastuximab tesirine, selinexor, anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy, and bispecific antibodies, such as glofitamab, have demonstrated promising efficacy and manageable safety profiles, offering potential new options in this difficult-to-treat setting.

References

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements:

The content was clear and easy to understand

The content addressed the learning objectives

The content was relevant to my practice

I will change my clinical practice as a result of this content